|

Home DH-Debate 8. Neolithic 10. Celtic Iron Age |

| 1. Introduction | 2. Geography and Climate |

| 3. Society | 4. Burial Mounds |

| 5. Religion | 6. Weapons |

| 7. Sailing | 8. Appearance |

| 9. Indo-Europeans | 10. Literature |

|

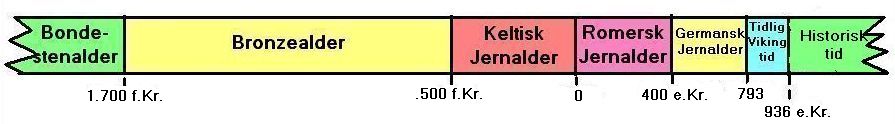

Timeline from Neolithic to historical time.

As the old hunters and the Neolithic farmers, the Bronze Age people preferred to live with view to water. The majestic Bronze Age mounds are often located on hills along the coast or along main rivers overlooking the glittering water.

The Stone Age farmers had already through two thousand years cleared the original forest and constantly increased the agricultural area. The Bronze Age farmers continued the work and in many places, they could look over wide open areas of scattered farms surrounded by vast pastures.

|

Left: The Bronze Age mound Kongshøj south of Kerteminde with a splendid view over Kertinge Nor.

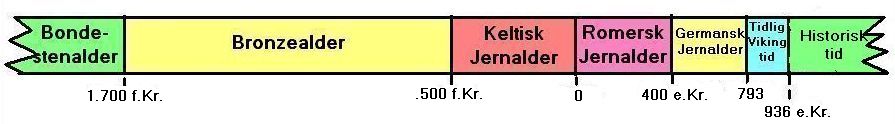

Right: The spread of the Nordic Bronze Age culture.

But there were still widespread primeval forests in central Sjælland, on Fyn and in parts of Eastern and North Jylland, not to speak of Scania. Only many years later - in the Middle Ages - the last primeval forests in Denmark were cleared.

Bronze is an alloy consisting of 90% copper and 10% tin. These metals were not naturally found in Southern Scandinavia. Each gram of metal had to be imported, but nowhere in Europe weapons and other objects in bronze were made in higher quality than precisely in Scandinavia, and nowhere else there have been found more ancient bronze objects per square kilometer than precisely here.

The Bronze Age was an aristocratic period with a big difference between high and low. Kings and princes had their quarters in large, probably splendid halls. They were surrounded by warriors with sharp bronze weapons, artfully decorated, and they were buried in large burial mounds, still present in the Danish landscape. How common warriors and peasants were buried, history does not tell us anything about.

|

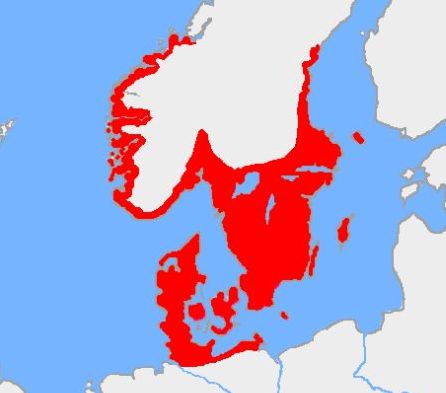

About 15,000 years ago - 13,000 BC - the ice sheet, that covered almost all of Scandinavia, slowly began to melt away. The reindeer walked to the north followed by the reindeer hunters. It is decided that the Ice Age in Denmark finally ended about 9,700 years ago. The green line represents the temperature on the surface of the ice. Dryas is the Latin name for the Arctic plant mountain avens, which is very hardy and the first to grow up after the ice has melted.

The temperature rose, and Denmark became completely covered by an primeval forest in which the Maglemose people hunted and fished. They were followed by the hunters of the Kongemose Culture, which with great certainty were the descendants of the Maglemose people. The following Ertebølle culture hunted and fished mostly along the coasts. Only in the Peasant Stone Age the people began to keep animals and cultivate the soil. About 500 BC the Bronze Age was replaced by the Iron Age's three periods. The Viking Age began with the attack on the monastery St. Cuthbert on the island of Lindisfarne in England in 793 AD and ended with the killing of Canute the Holy in 1086 AD in Odense. The Middle Ages ended in 1536 with the Civil War, the Count Feud, and the Lutheran Reformation.

In the Bronze Age, the climate was warmer than the present, but not quite as

warm as in the Hunters Stone Age. The Minoan warm period occurred around the middle of the Bronze Age, and lasted several hundred years.

In 60% of Denmark's history, the main occupations have been hunting and fishing. In 75% of the time has been a kind of Stone Age.

In the Bronze Age, millet was grown in Denmark.

The Bronze Age coastline was roughly the same as today. However, one must believe that South Jutland's west coast was farther west than in the present, as the land south of the line Nissum Bredning - Falster has fallen since the last ice age. Perhaps the land at the southwestern coast was 4-5 m. higher in the Bronze Age than today. Tourists have found Iron Age pottery washed ashore on Rømø's southern east coast out of Rømø Sommerland, which also supports an early more western coastline.

In contrast, Rømø and other North Frisian islands were smaller in the past, since they largely are formed of sand, which over time had been led to there by the current. Large areas in West Jylland and Thy, which today are covered by sand drifts, were back then lush pastures in rather densely populated areas.

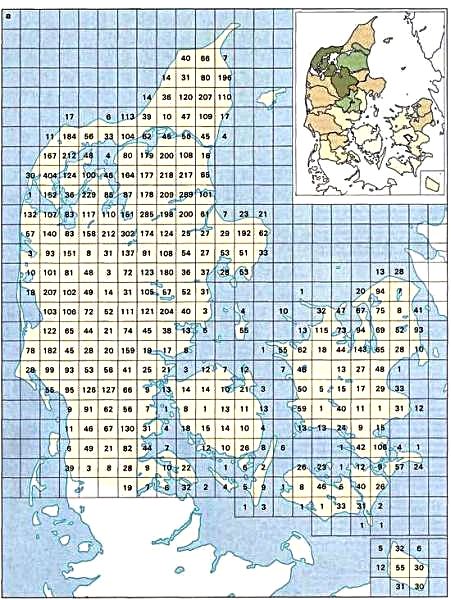

The density of Bronze Age burial mounds, which are higher than two meters. Each square is 100 km2. It is seen that the mounds are close located in North Jylland and Thy, while there are very few mounds on central Fyn and Sjælland. One can not immediately conclude that a small number of mounds means that the area was sparsely populated, as intensive agriculture has led to that many mounds have been plowed. In Denmark are registered nearly 40,000 burial mounds from the Bronze Age - Historisk Atlas Danmark bt J.K. Hellesen & O. Tuxen.

In the middle of the Bronze Age occurred the Minoan warm period that lasted several hundred years. Not much is known about this warm period beyond what can be measured in cores from the ice cap. It has its name because it coincided with the Minoan culture of Crete.

That the climate really was warmer then may be derived from the fact that in the Bronze Age millet was grown in southern Scandinavia. Millet is grown today in tropical and subtropical regions; it is an important crop in Asia, Africa and in the southern United States. The annual average temperature in Mississippi and Alabama are around 10 degrees, which to be compared

with today's annual average temperature in Denmark, which is 8 degrees. So maybe the climate in the middle of the Bronze Age was around 2 degrees warmer than in the present.

Archaeologists have so far not found any indications that parts of buildings have been used to have cattle in a barn during the winter, as is clearly was the case in the subsequent Iron Age. Most likely the cattle were out all year.

The primeval forest, which still covered much of the country, was dominated by small-leaved linden mixed with hazel and oak. On moist soils and wetlands also other tree species were found like elm, ash and el. In western Jylland the forests were mixed with birch. In the Bronze Age, beech immigrated to Denmark, but it was not very common in the beginning.

The forests covered mainly hilly and difficult cultivable land, like the central North Sjælland, Himmerland, central Fyn and central Sjælland. However, landscapes with flat terrain, fertile soil and rich in clay, such as Thy, the northern Fyn Plain, West Sjælland and the area between Køge and Roskilde, were early utilized for farming and cattle breeding.

Already the Neolithic Single Grave people took advantage of the plains of western Jylland for grazing cattle, perhaps sheep and goats; they maintained the heath by burning, a practice which continued in the Bronze Age.

In the Neolithic period, the dead were buried in common graves, which are called Jættestuer (passage graves); it is assumed that all came in the same grave, indicating a society, where people were quite equal. The Bronze Age, however, was an aristocratic society, where important people, probably kings and princes, were buried in large burial mounds. They were most often build in prominent locations, for example on hills at the coasts or along major roads. Most mounds were built in the first half of the Bronze Age, but there were built burial mounds until around 1000 BC, and many of them still exist.

|

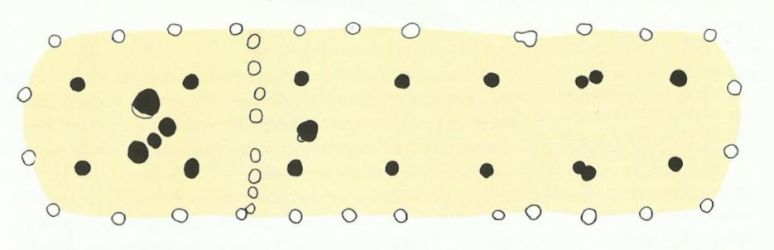

Plan of the postholes from a Bronze Age house at Højgård in Southern Jylland. There have been found no remains of houses from the Bronze Age, but there have been found many post holes, which give indications of size and construction. The white holes are connected to the outer wall, and the black holes indicate roof bearing inner uprights. There is also random holes, which are not connected to the housing construction.

Already from the late Neolithic period have been found very large houses, which can be interpreted as local kings' or princes' halls, such as findings from Limensgård on southern Bornholm. In the Bronze Age that kind of princely halls became more common. At Egehøj in Jylland, at Trappendal near Gram in South Jylland, at Hyllerup near Slagelse and many other places, have been found postholes from houses with several hundred m2 under roof. The largest had a length of 44 m. and a width of 8 m. which gives a floor plan of about 352 m2.

|

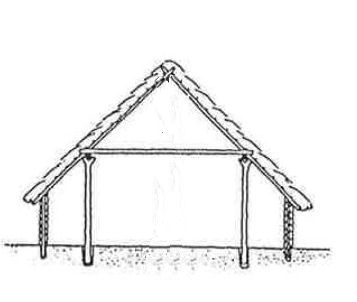

Upper left: Reconstruction of cross-section of Bronze Age house with two rows of inner

roof-bearing posts. One can imagine that the area between the outer wall and the nearest row of posts was sleeping places.

Upper right: Urn from the Bronze Age found at Stora Hammar near Skanør in Scania. It is painted as a sort of house. Similar urns have been found throughout the country and in large parts of Europe. Especially previously it was assumed that they expressed how houses in the Bronze Age really looked like.

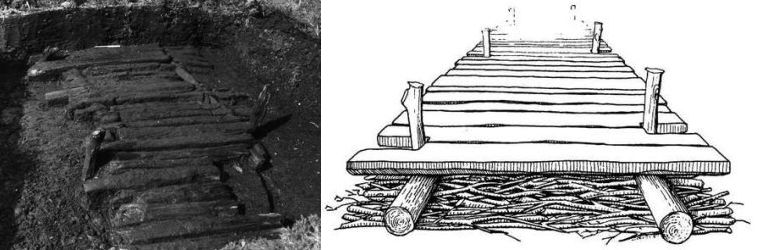

Below: Plank road from late Bronze Age around 800 BC through a swampy area in Skalså valley north of Viborg. It's built with split oak logs that have been placed on the soft soil, so they made an up a 2.5 meter wide road. The road stretched 215 meters through the swampy area down to the Skals Å, where there must have been a crossing option or perhaps a bridge.

As a general rule, the houses were built with two rows of longitudinal inner roof-bearing posts in addition to the posts in the outer walls. It's a design that was to last for a thousand years and still can be found in old farmhouses. This testifies skillful carpentry in the Bronze Age.

Some have calculated that there was a distance of approximately 12 km between such princely halls.

The probably splendid halls and the numerous finds of gold from the Bronze Age testify that it was a rich society. From the beginning of the period have been found rings of double gold wire, and from the Late Bronze Age have been found the so-called oath rings, which are massive golden arm rings with bowl or knob-shaped ends.

|

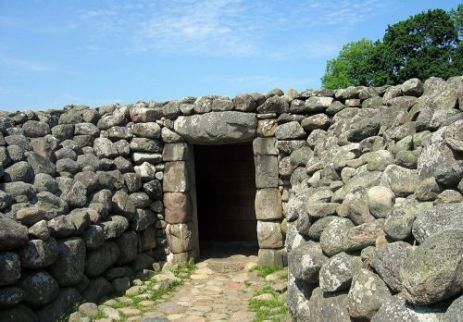

Left: Entrance to the stone grave at Kivik in Scania north of Simrishamn.

Right: The Dying Gaul - King Attalos of Pergamon defeated a Gallic tribe and erected a trophy in his capital around 230 BC. The original was made of bronze; this is a copy from Roman Imperial times from a Capitol museum in the United States. The Gaul bears a neck ring of twisted gold threads with knobs as those of which have been found so many from the Scandinavian Bronze Age. They are called oath rings because it was previously thought that they played a role in swearing.

The Scandinavian princes surrounded themselves with a wealth of finely crafted bronze and gold objects. Nowhere else in Europe have been prepared weapons and other items in bronze of a higher quality than in this particular region. The Danish finds from the Bronze Age are numerous and unique.

|

Rings of gold with knobs of the type which is called oath rings found at Boeslunde. If one adds together the weight of all of the about 10 gold rings, which were found in the area, it makes up to 3.5 kg. Photo Sjællands Museum.

We know the old saying: "From Arild's time" (from time immemorial). In Harrislee west of Flensburg a large Bronze Age burial mound is called King Arilds Mound, which some believe may be ascribed to that a powerful Bronze Age king named Arrild is buried here. It is said that also in Scania is a king Arild Mound. Actually, there are strikingly many burial mounds from the Bronze Age, which from ancient times have been called something with king, for example King Svends Mound at Egedal, King Ran Mound at Randbøl, King Dags Mound in Scania, Kongshøj (King-Mound) at Kerteminde and so on, a legend tells that King Ho is buried in Hohøj. It is very likely that the mounds are the final resting places of aristocratic princes and local kings.

At Kivik in southeastern Scania is the largest Nordic Bronze Age grave. It is made of

stone, and some have calculated that 200,000 wagon-loads stone had been used for the construction. This shows that there already was a strong central power in the Bronze Age in Scania 3.300 years ago. The burial chamber is decorated with pictures of spoked wheels, axes, ships with people on board, lur players and much more.

|

Plank road from the Bronze Age through Speghøje Mose. To the left as it was during

excavation and to the right a reconstruction. The originally 300 m long road led in early part of the Bronze Age over Pårup bog area's narrowest point.

All copper and tin had to be imported, most likely from mines in the Danube valley,

mainly in present Hungary.

It is uncertain what was exported in exchange for metals, but many guess amber - who knows, it may also have been slaves.

International trade had taken advantage of a network of paths that one today can find traces, where they have passed wetlands. In Jutland in Speghøje Mose and Skalså valley, ancient roads from the Bronze Age have been found.

Bronze Age burial mounds were all built of grass turfs, which were peeled off from the nearby fields. The turfs were usually 40 to 60 cm long and about 10 cm thick. They were placed with grass downward. It has been an expensive pleasure for the Bronze Age people; peeling of grass turfs must have made large areas useless as pastures for decades to come.

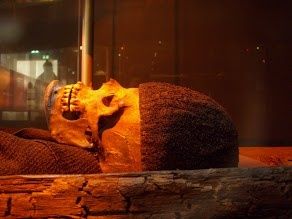

The Egtved Girl in her oak coffin, as she is on display at the National Museum. She was found at Egtved north of Vejle.

From well-preserved oak-coffin graves from the Early Bronze Age, we know that the deceased were buried fully dressed, covered with a woolen blanket and wrapped in a cowhide. Depending on whether the deceased was a man or a woman, the dead got weapons, jewelry, toiletries, extra garments, a clay or wooden vessel with a beverage and in one case a folding chair as grave goods. Sometimes archaeologists have found small pieces of burned human bones together with the unfired body that probably should be interpreted as a human sacrifice in a funeral ceremony.

The deceased were often laid to rest in a coffin of a hollowed oak that was covered with a layer of stones, which were sealed with clay. On top of this the mound was built.

Hohøj near Mariager is Denmark's largest burial mound. It is 12 meters high and has a

diameter of approximately 71 m. The volume of the mound has been calculated to more than 16,000 m3. It is built of grass turfs, which have been stripped of the pastures in its immediate vicinity. Some have estimated that more than 200,000 m2 grass area has been made useless as grazing for livestock because of the construction of the mound. This corresponds to the area of 31 football fields.

Hohøj near Mariager seen from southwest.

Near Tobøl at the river Kongeåen between Esbjerg and Kolding is the large mound Skelhøj, which was built around 1,350 BC. On the opposite bank of the stream, several settlements from the same time have been found.

Parts of the mound were excavated and carefully examined in 2002-2004. It was evident that it was built by many layers of grass turf laid with the grass side down. During the building, the mound had been divided into four sections or shells outside each other, which were about 1.5 m. thick; these had again been divided into sectors that defined the areas of different work teams. It could be seen that the various sectors of the shells consisted of different types of turf, which were taken from various areas. Each work team must have had had their own paths and ramps into the mound-building area, and they picked up the turf in their own part of the landscape.

Many mounds have been surrounded by a circle of big edge stones, a path of stone paving, a deep trench or there may be traces of a fence of wooden posts.

East of Skelhøj was found a place on which there had been a contemporary building about

8 m. wide and 13 m. long with walls of wooden planks and two rows of inner roof-bearing posts. The house had likely looked like the contemporary princely halls, but it has been very short, therefore, it is assumed that it had a particular purpose, perhaps as the scene of celebrations in honor of the ancestors.

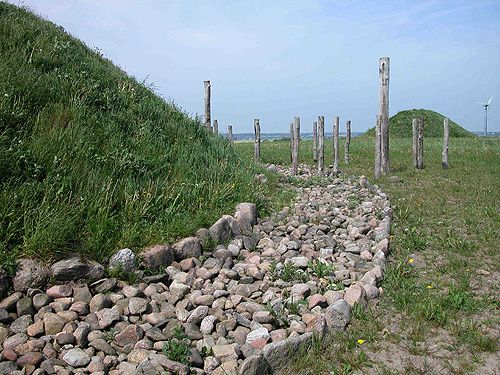

Reconstructed stone paving around a Bronze Age mound near Borum Eshøj north-west of Aarhus. It has been demonstrated that many Bronze Age burial mounds originally were surrounded by stone circles, stone pavements as here, plank fences or deep trenches.

Some Bronze Age mounds are flat on top and have most likely always been. Locals call them dancing mounds. One can imagine that the Bronze Age people had held ceremonies in honor of the ancestors on top of such mounds.

In the late Bronze Age after 1,000 BC, a new and much simpler burial custom was introduced. The dead were burned, their bones were gathered from the ash and put into a clay urn with very few grave goods. The urns were dug into the south or east side of the old mounds. This is in sharp contrast to the early Bronze Age's mighty mound burials and rich grave goods.

The transition to cremation took place almost simultaneously throughout Northern Europe, and must have been connected with the spread of new religious ideas - but perhaps also with diminished wealth and a changed social order. Maybe they thought that only when the body was burned, the soul could be released and travel to another world.

But they still felt a connection to the ancient burial mounds and perhaps had the idea that when the deceased's urns were inserted into the famous old king's burial mound, their souls would join him in the other world.

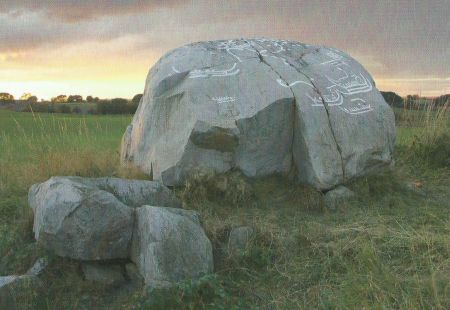

Rock carvings from Bronze Age on a jættestue (passage grave) from the Neolithic period at Gladsax in Scania.

At the introduction of Christianity in Scandinavia around the year 1,000 AD, the whole of the former gallery of gods and heroes was replaced with the Christian God, Jesus, the Virgin Mary and The Holy Spirit. It is not likely that former religion changes have taken place in this way. The believers may have meant that the former gods still existed, but only they were not as powerful as the new gods. They may have given the new gods some of the old gods' qualities or worshipped the new gods in ancient sacred sites.

At Gladsax in Scania and on the south of the island of Bornholm are several carvings on capstones of passage graves from the Neolithic period, which testify that the Bronze Age people still considered the dolmens to be holy places. Inside the chamber of the passage grave Jættedal, in Aaker on Bornholm is a small figure carved in cup marks, which forms the star constellation the Big Dipper on one of the supporting stones. On capstones and boundary stones in Rynkebjerg jættestue near Vordingborg, Busemarke langdysse at Stege, Jordehøj jættestue on the island of Møn, Sprovedyssen at Vordingborg, the Dystrup Sø dolmens on Djursland and Sømarke Dolmen also on Stevns have been found traces of up to 458 carved cup marks from the Bronze Age.

Left: The star constellation Orion made with cup marks on Madsebakke near Allinge on the island of Bornholm.

Right: The star constellation the Pleiades made with cup marks in Baimiaozi Mountains near the city of Chifeng in Inner Mongolia.

Cup marks are the absolutely most frequent rock carving; they must probably be counted in tens of thousands. The significance and the meaning of them is unknown. We can imagine everything, yet we know nothing. But let us imagine that they had a function in the annual ceremony for the ancestors. Every year a new cup mark was chiseled on an ancient sacred site and perhaps food or the like was placed for the ancestors. Some creative priests carved cups year after year so that they in the end formed star constellations.

In Neolithic they placed sacrifices to the gods in bogs and lakes, and this continued during the Bronze Age - and the Iron Age - the Sun Chariot, the lurs and numerous other bronze objects have all been found in bogs or former marshes and lakes, where they have been placed or immersed as sacrifices to the mighty gods, who lived around this water, and whom they had the habit to worship. It is easy to imagine that they are the origin of the family of gods that the later Vikings called Vanir, as "vane" means "habit" in Danish.

Before 1903 a celt was found at the south shore of Tranemose at Raklev near Kalunborg in connection with peat-cutting. On the same site also the edge part of a grinded flint ax from Neolithic has been found. This suggests that sacrifices were made in the same place for thousands of years, but of course, it can also mean that they still used stone axes in the Bronze Age for various daily jobs.

|

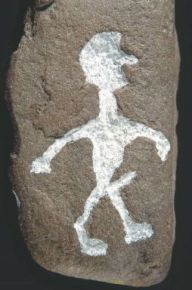

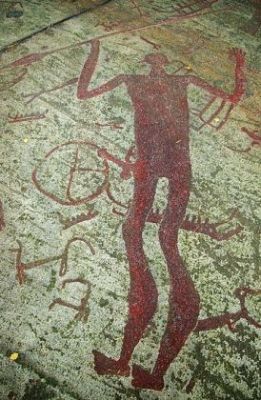

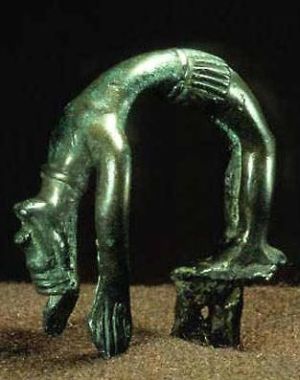

Gods and heroes came and left, but there was also continuity in religion, through six

millennia men or gods with large erected phallus represented vitality and fertility.

From left to right:

- The dancing man from Bodal - Ertebølle Hunter's Stone Age.

- A Man with big phallus and a big fish in an image on a stone found at Horsens Fjord near

Ertebølle settlement.

- Incising of a man with erected penis and a woman on an urn cover from Maltegårds

Mark near Gentofte - Bronze Age.

- The Broddenbjerg man, who was found in a peat bog at Broddenbjerg near Viborg. He

is Carbon 14 dated to the late Bronze Age. Photo: Lennart Larsen.

- The god Freyr with a large phallus from Rällinge, Södermanland - Viking Age.

They had no written language, and there are not preserved legends, which with certainty originates from the Bronze Age; but they left a wealth of images in the form of tens of thousands of carvings, bronzes and carved images on these, and from these we can sense

the contours of a religion, in which the Sun was in the center. All the rituals depicted on the carvings and bronze objects may have been intended to ensure that it reappeared every morning and that it every spring regained its power and made the crop on the fields, the leaves, flowers and insects to be born again.

|

Top left: Petroglyph on a rock from Truehøjgård in Himmerland, which represents a man with an erected penis.

Top right: In 1902 Frederik Willumsen found the unique Danish Bronze-treasure, which is

called the Sun Chariot, in Trundholm Mose in Odsherred on Sjælland. It measures 59 cm. in length. It is perhaps a model of a real cart.

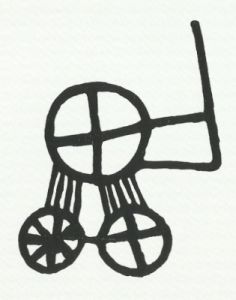

Below: Petroglyph from Backa in Brastad parish in Bohuslen, which can imagine a sun symbol placed on a cart with four wheels. The sun is a so-called wheel-cross, the front wheels have four spokes, as a wheel cross, but the rear wheels have six or seven spokes. As it is said, we know nothing, but one can also imagine that it illustrates something more philosophical, namely the great cycle (World Year), which is divided into four periods, which are the year's cycle, that in turn is divided into the four seasons, and a smaller cycle controlled by the lunar phases of perhaps 6-7 days all causally connected, as illustrated by lines.

It also seems possible that the Aesir gods such as Odin, Thor and Freyr, had their closely related ancestors in the Scandinavian Bronze Age, although their names and mythologies may have changed over the millennia. The other alternative - that all deities and stories of the Bronze Age disappeared without a trace, and new gods took their place - seems less plausible.

The Sun Chariot consists of a bronze hollow-casted horse, drawing a sun disc coated with gold and decorated with circular motifs. The horse and the disc stand on six wheels each with four spokes. The solar disc is gold plated on the right side in the driving direction and matte on the other side. The spiral ornamentation on the disc tells that the Sun Chariot was made in Scandinavia around 1,350 BC. It was destroyed before it was deposited in the bog as a sacrifice to the gods.

The Danish archaeologist Flemming Kaul has proposed that a movement from left to right

symbolizes the day, in the same way as we see the sun moves from east to west on the

southern sky. The opposite movement from right to left symbolize the night, which explains the two different sides of the solar disc on the Sun Chariot, because the right side is golden, and the left is matte.

|

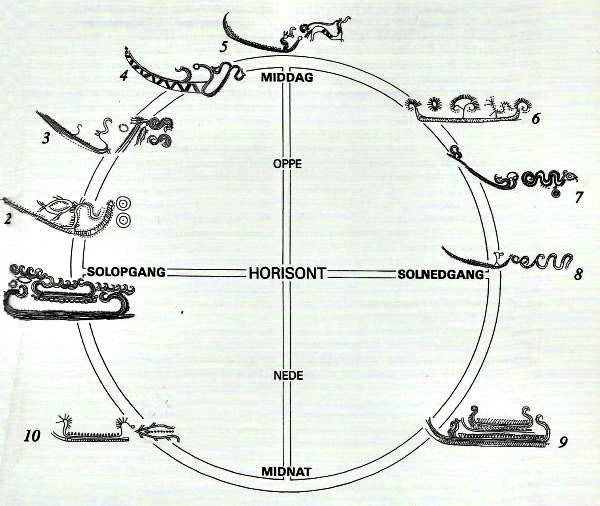

Top: Flemming Kaul's reconstruction of the Bronze Age mythology based on motifs

on razor knives:

1. Fish helps Sun from night- to morning-ship - Unknown finding place. Moesgård Museum.

2. Fish sails with morning ship - private ownership.

3. Fish is eaten by a bird before horse retrieves sun - Found at Torupgård Mark. Moesgård Museum.

4. Sunhorse pair retrieving the sun from ship. Found near Skive - Langelands Museum.

5. Sun horse has taken over sun from ship - Found at Neder Hvalris. National Museum.

6. Horse delivers sun to ship - Found at Vandling Sønderjylland. National Museum.

7. Snake has taken over the sun from ship with horse. - Found on Lolland. Museum in Maribo.

8. Snake helps sun down, tucked in the tail curls.

9. Night vessels without visible suns. Found near Jelling. National Museum.

10. Night ship and fish, ready to help the sun up. - Found on Møn. National Museum.

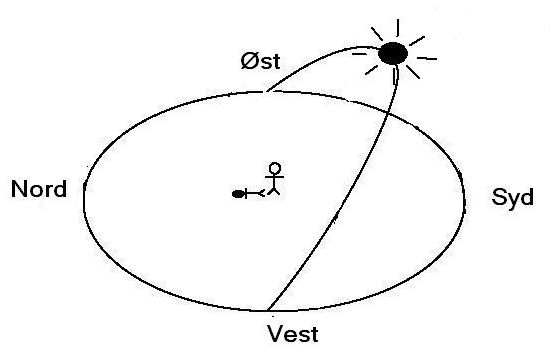

Bottom: The sun's path in the sky. When we look to the south, the sun will move from left to right. When the horse pulls the sun across the sky from left to right, we will see

the sun disc's right side, which is gold plated on the sun chariot.

From "Bronzealderens Religion" by Flemming Kaul published by Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

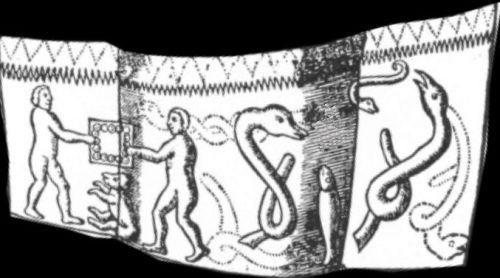

Flemming Kaul has examined all known images from the Bronze Age from carvings on razor knifes to petroglyphs and demonstrated clear indications of, where various animals and objects are placed in relation to the sun's daily cycle. He came up with that the Bronze Age people imagined that the sun was pulled across the sky in the daytime of various helpers. In the morning in the east, a fish brought the sun onboard a ship that carried the sun until noon. From at noon, when it is highest in the sky, the horse pulled the sun and delivered it to an afternoon ship. In the evening a snake brought sun down in west to the underworld, which was below the flat Earth. Down here, the sun was dark, while it on the night-ships was brought back to the morning's eastern starting point, where the fish again took over. During the night the sun would thus move through the underworld from west to east exhibiting the left-hand side of the solar disc, which is dark. Thus the daily cycle repeated in all eternity, maintained by the Sun's helpers - fish, horse, snake and ships.

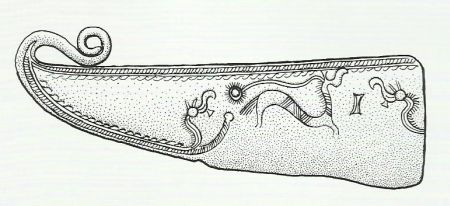

Bronze razor knife from Neder Hvolris north of Viborg. Sun horse pulls the sun in a line - without wheels. Drawing by Bjørn Skårup.

But we have no certain knowledge. The later Viking myths tell that the sun was pulled by horses all the way.

It is reasonable to believe that the Sun Chariot horse was an ancestor of the horses Alsin and Arvak, which in Viking mythology pulled the sun across the sky. Also, another Norse myth tells about the sky-horses Skinfaxe and Hrymfaxe that pulled respectively sun and moon.

We can also think that the snake is a forerunner of the Viking Age's Midgard Worm. According to the Edda the worm is in the World Sea, and it is so large that it can surround the whole Earth and grasp its own tail. At that time it was believed that the Earth was a flat disk, like a pancake, which was surrounded of the World Sea; it will then cause the worm encircling the flat Earth, and the sun must pass it both at sunrise and sunset. However, according to Flemming Kaul's analysis, the sun has only contact with the snake at sunset. Perhaps the Midgard Worm was not so big in the Bronze Age.

|

Left: Most petroglyphs with wheel cross are found at Lille Strandbygård in Nylars on the island of Bornholm.

Right: Bronze wheel found in a tomb from the Early Bronze Age at Tobøl north of the stream Kongeåen. It has precisely four spokes, like the wheel crosses.

Wheel cross is another very common rock carving. Many believe that it is a Sun Sign

because a few petroglyphs from Bohuslen show a horse pulling a wheel cross. There are also petroglyphs with wheel cross, which can be interpreted as the sun being transported on a ship.

But it can not be explained away to the figure looks like a wheel with four spokes, and the most obvious interpretation is to assume that it actually depicts a wheel with spokes, one of the Bronze Age's technical innovations.

It may have represented the Wheel of Time, which is the belief that everything in the world will be repeated in various longer or shorter cycles, which is also a function of the passage of the sun. When you put a mark on a wheel and let it rotate, you will see that mark again after each revolution. When the wheel rotates, we see the same marks and shades come again and again with each cycle.

|

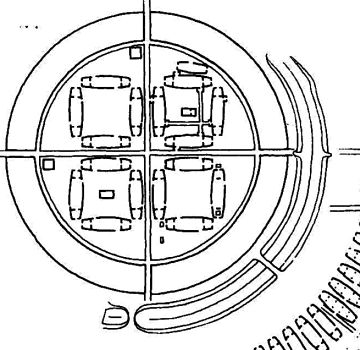

Left: The late Viking period's trelleborg type strongholds' layout was just like a wheel cross. It is in fact not optimal from a military point of view because from a given point on the outer wall one has no overview of other parts of the wall. A square fortification with corner towers would have been much more suitable. Maybe the layout was chosen because it represented the ancient faith.

Right: Wheel Cross motif on wooden stool found at Høstad on Bynæsset near Trondheim in 1899. Dated to about 470 f.Kr.

The day wheel is driven by the sun. Each turn is virtually the same, the birds wake up, the sun rises, it reaches the dinner altitude, go back down, darkness falls and the moon and the stars take their turns.

When the wheel of the year takes its course, the same will happen again at every turn. The length of the day increases, the sun's heat increases, the snow melts, the insects resurrect, the migratory birds return. That is how at every revolution of the sun and the stars.

|

Rock carvings at Aspebjerget near Tanumhede in Bohuslen - They imagine right and left sailing ships, deer and cattle, an archer, a snake, a man plowing with two oxen, a picture of the sun and some human figures, which can be identified as men due to their erected penis.

The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus, who lived at the transition from the Bronze- to iron-age (born 540 BC) in present Asia Minor, said that time was divided in "world years", which was the time between two "World Fires". During each "world year", stars and planets would run through exactly the same orbits as in the previous "world year". His theory was taken up by the later Stoics, who wrote that in each "world year" everything would repeat itself; "the same Plato would teach in the same Academy in the same Athens".

The idea of the time, which runs its course in large and small cycles in which everything repeats itself, can be found in surviving Buddhist texts that have Indo-European roots, probably back to the Bronze Age. In fact, this idea may not be so different from that worshipping the sun, because it is the sun that controls the eternal returns.

In Alvismal from the Poetic Edda is told that the elves called the sun "Fager-hjul" (Fair Wheel).

Thor spake:

"Tell me, Alvis!

everything in life

I expect, dwarf! that you know

What is the sun called that all men see,

In each and every world?"

Alvis spake:

"Men call it "Sun", gods "Sunna",

"The Deceiver of Dvalin" the dwarfs;

The Jats "The Ever-Bright", elves "Fair Wheel",

"All-bright" the Aesirs descendants

We can send our thoughts to the medieval ballad Elverhøj and the myth of the Elves living in the mounds:

I put my head to Elverhøj,

My eyes they got a rest;

There came two virgins forward.

They would like to have a talk with me.

There are thousands of wheel crosses, which we can call "fair wheel", all carved by the

Bronze Age people, who also built the burial mounds. So maybe it's true that it is the

Elves, who live in Denmark's thousands of burial mounds.

Further in the Poetic Edda "Sigurdrifa's Kvad" speaks about a shining god, who rolls on

wheels:

"Poems were then written on shield

which stands for shining god,

on Aarvak's ear

and on Alsvinns hoof,

on wheels that rolls.

with Hrogne's cart,

at the loins of Sleipner

and carriage's bolts.

And also in the Edda's Vavthrudnesord the sun is called "alv shine", that is elver-shine. Moreover, we note that the word sun is femininum, as it also was in many old Danish dialects and still is in German:

Encst daughter

Alv shine gives birth,

before Fenre gets her;

I wonder if she gives birth,

when powers die,

the virgin, her mother's way.

We still believe in our hearts that everything repeats itself. Every year we celebrate our

birthday. What happened many years ago, a particular child was born, is repeated year

after years in new guises. Every year we mark the anniversary of our wedding and other

private and national anniversaries.

|

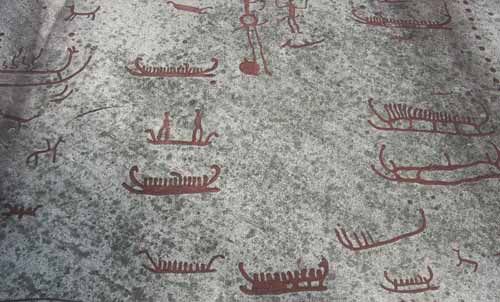

Top: Left-sailing ship in the Vitlycke rock carving field near Tanum in Bohuslän. At Vitlycke are several fields that are listed on the UNESCO list of World Heritage. Ships are the most frequent rock carving motif. These ships sail against left and are all without sun symbols.

Bottom: Right-sailing ship with sun-symbols at Solbakke Strand a little north of Jørpeland near Stavanger in Norway.

Ships were a very frequent motif in the South Scandinavian Bronze Age. There are thousands of petroglyphs depicting ships and they are a common motif on bronze razor knifes, of which also many have been found. For example, half of Bornholm's petroglyphs depict ships.

Flemming Kaul has analyzed ship images on Danish bronze objects and found that 97 ships are sailing to the right while only 26 of the ships are sailing left. By comparing with the sun chariot and the sun's path in the sky, seen to the south, we can conclude that the 97 ships are sailing to the west and the 26 against east. The motives that are attached to the respective right and left sailing ships are different, indicating that the sailing direction is not random. As many as 41 of the right-sailing ships have attached circles, which can be interpreted as sun symbols, while not a single ship sailing to the left is attached with sun symbols.

Right-sailing ships from the petroglyph field at Bardal in Steinkjer, a few hundred kilometers north of Trondheim. The upper one is attached with sun symbols and has a crew of about 100 men, and the bottom one has about 40 men onboard. The lines representing the crew are not very regular, some are larger than others, and there are passengers under deck, and even in a kind of lifeboats. One can get the idea that every time a man in the village died, he got carved a place on a ship, sized according to rank and position.

It can be understood, as the ships that sail to the west helped the sun on its way over the sky, as was the case in the Egyptian religion; alternatively, the sun symbols show that the ships on their way west are sailing on a sea where the sun shines - unlike the underworld.

Ancient Celtic and Greek legends tell about the islands of the blessed in the western ocean. Homer song about Elysium, which lay at the Earth's western edge at the river Orkanos. Hesiod song about the fortunate islands, which lay in the western ocean at the end of the world. In all cases, it was something about that the deceased left this world and sailed to the west, such as Tolkien describes the Elves' departure to the west in the end of "Return of the King".

Therefore, one can allow ourselves to believe that the ships, which headed to the west, carried the souls of the deceased.

But what about the left-sailing ships, which we believe sail to the east?

The fish and the snake appear on the Bronze Age images - perhaps as the sun's helpers or guardians of the eastern and western horizons. They also appear on the golden horns from the iron age many centuries later - From verasir.dk

The Bronze Age people can - as little mother in the old play Erasmus Montanus - have believed that the Earth was flat as a pancake. Every morning the sun rose over the world's eastern edge, and every night it sank down below the western edge. When the sun during the day traveled to the right it shone, like the sun discs' right side on the Sun Chariot, and when the sun at night traveled to the left through the underworld back to the world's eastern edge, its lights were turned off, as the sun discs' left side.

None of the 26 left-sailing ships are attached with any sun symbols, which must mean that they sailed in darkness through the underworld as they followed the route back to the worlds' eastern edge, where the sun would rise again, as it does every morning.

If one thinks that the whole world is governed by cycles that return in themselves and that everything will repeat itself and come back in new forms, then there is only a small step to believe that also a human life is something that will happen again.

We can also find inspiration for an understanding of the ship pictures of the bronze age in Homer's epic, Odysseus, which tells the story of the Phaeacians' magical ships. The poem is about the hero Odysseus' journey home from Troy precisely in the Bronze Age; it is assumed to have taken place around 1,200 BC. The journey home lasted for ten years and required tremendous hardships and difficulties.

|

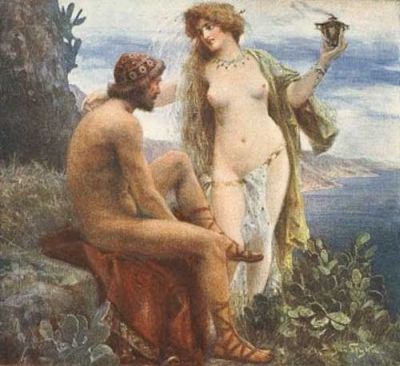

Left: The nymph Calypso offers Odysseus immortality - painting by Jan Styka.

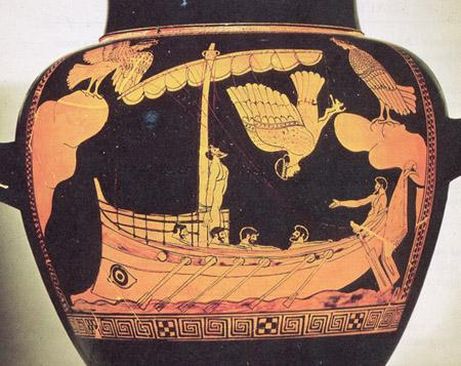

Right: Odysseus on his ship shown on a Greek vase from the fifth century BC. Here we

see steering oars.

After losing all his ships and all his men, he was washed up on the beach on the island of Ogygia, the navel of the sea, where he was held back by the nymph Calypso, daughter of the titan, Atlas, who gave name to the Atlantic Ocean (Herodotus: Atlantis Thalassa). Many believe that the island was located in the Atlantic Ocean, that is the western ocean and not the Mediterranean. By magic, Calypso kept him as her lover for seven long years, but in the end, he succeeded to escape on a raft to the neighboring island Scheria, which we must assume also was located in the Western ocean. The Phaeacians lived on Scheria.

The Phaeacian princess Nausicaa describes the location of their island: "Far away we live by the sound of the rolling waves, and no other mortals know about us."

Motif on a Greek vase from 660 f.Kr showing a fight between a Greek and Etruscan ship.

The design of the ships reminds of the ships on the Scandinavian rock carvings. It is clearly shown that they have steering oars and that they are being rowed and not paddled.

Some have derived from Homer's poem that there was tide at the shores of the Scheria island. This will exclude the Mediterranean, where the tide is insignificant.

King Alkinoos of the Phaeacians said to Odysseus: "I will appoint tomorrow as the day. While you are sleeping, they will row you over the shiny sea, until you come to your own house and land, or wherever else you want to go, even if it is outside Euboea. Those of our people who brought the yellow-haired Rhadamanthus to visit Tityus, son of Earth, saw the place and call it the end of the world. They sailed there, without exertion, completed their task and returned home the same day. So you can realize that my ships are the best, and my young men the most excellent to drive the oars through the salty waters."

|

Rock carvings with ships at Blåholt Huse on the island of Bornholm - In none of the Nordic petroglyphs depicting ships is shown something that convincingly may look like rudder or steering oar.

"Tell me about your country, nation and city, that our ships can form their purposes

accordingly and bring you there. For the Phaeacian has no navigators; their vessels have no rudders, as other nations' have, but the ships themselves understand, what we think and want, they know all cities and countries around the world, and can cross the sea, even when it is covered with fog and mist, so there is no danger of dying or having injuries."

"The ship bounded forward on her way, as a four in hand chariot flies over the course when the horses feel the whip. Her prow curveted as it were the neck of a stallion, and a great wave of dark blue water seethed in her wake. She held steadily on her course, and even a falcon, swiftest of all birds, could not have kept pace with her. Thus, then, she cut her way through the water, carrying one, who was as cunning as the gods, but who was now sleeping peacefully, forgetful of all that he had suffered both on the field of battle and by the waves of the weary sea." The Phaeacians' ship left Odysseus sleeping on the coast of his homeland, Ithaka.

Thus, the Bronze Age people could have perceived the rock carving ships - as magical ships, which due to the power of thought and faith could bring the dead sleeping to the world's western edge, through the underworld to the eastern edge and resurrection - as the Sun, Moon and some of the stars are born again in the eastern horizon.

Tacitus mentions many hundred years later in his Germania that "some are of the opinion that also Ulysseus during his long and legendary migrations traveled in these parts of the ocean and visited the countries of Germania and that Asciburgium, located on the banks of the Rhine, and still today is inhabited, was founded and named by him. Not only this, but they also say that an altar, which was inaugurated by Ulysseus, adding the name of his father Laertes, once was found in the same place, and that certain monuments and burial mounds inscribed with Greek letters still exist in the borderland between Germania and Raetia."

|

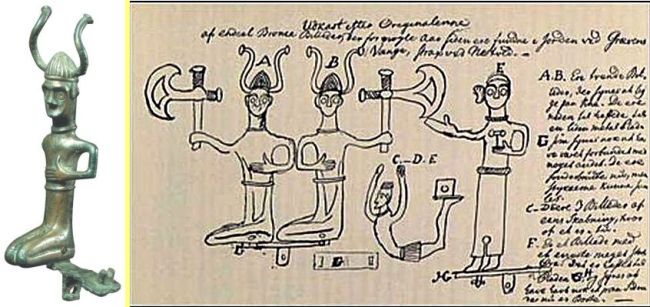

The Bronze Age finding from Grevensvænge near Næstved, reproduced by Marcus Schnabel. In the year 1700 at Grevensvænge on Sjælland a small bronze figure was found that imagined a twin pair with horned helmets and axes in their hands. However, the pair was separated and one ax-bearing figure was lost, most likely during the bombardment of Copenhagen in 1807. However, the Norwegian priest Marcus Schnabel had made a drawing of the finding.

We have no certain knowledge about the religion of the Bronze Age, all this is pure speculation. In Scandinavian history and culture are no direct references to rebirth. However, it seems to me that the ancient custom of naming children after deceased relatives represents a belief that ancestors can be reborn in new generations inside the family.

The closest one can get concrete statements about the idea of rebirth in Bronze Age

Europe is a note at Caesar on the Druids' doctrine: "First of all they learn that the

soul does not die but wanders from one to another after death, and they consider it

a great incentive to bravery that the fear of death thus is removed". Some believe

that Caesar has got this information in a lost work on the Celts of the Stoic philosopher

Poseidonius. But as Caesar himself for years stayed with the Celts in Gaul, it is

reasonable to believe that he had this information from themselves.

Several have tried to connect the Bronze Age characters with the later Viking gods based on their weapon of choice. Thor is characterized by his hammer or ax, Odin preferred his spear Gungnir, and Freyr is known for his good sword, which he gave away to have the beautiful Jotun girl, Gerd, in marriage.

|

From top and downwards:

- Rock carving from Sotetorp near Tanumshede in Bohuslen showing a right-sailing vessel

manned with 13 men and two mythical figures with horned helmets and big axes, both with

significant phallus. A person makes somersaults along the length of the ship. The ship has dragon- or horse-head in the bow.

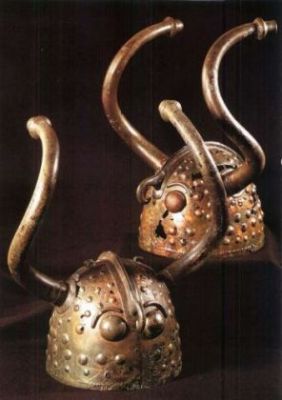

- Two horned bronze helmets were found in 1942 by peat cutting in Veksø Mose between

Roskilde and Frederikssund. They are obviously unfit for military use and must have been

used in religious ceremonies.

- Two very large ax heads of bronze from around 1,400 BC found at Egebak near Thisted in Northern Jylland. They are each 50 cm. long with a weigh of 7 kg. They are elaborately

decorated with spiral patterns. They are clearly too clumsy for military use and may

have been designed for use in religious ceremonies.

- Petroglyph at Litslebyhällen near Tanumhede in Bohuslen. A large man armed with spear and with erected phallus is called "the spear-god rock carving". Many believe that it represents an early Odin with the spear Gungnir.

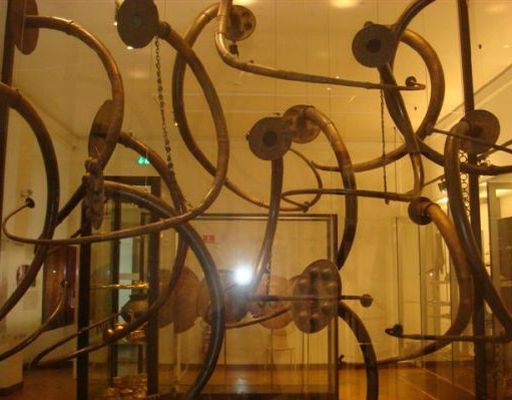

- Bronze lurs on display in the National Museum. The lurs testify the masterful molding technique of the Bronze Age. Foto: Kees Kaldenbach.

- Petroglyph at Kalleby in Bohuslen, showing three potent lur players.

From rock carvings, we know a mythical pair of twins with horned helmets and large axes. We know this figure from several depictions on petroglyphs, and there have also been found real horned helmets and big axes. The real axes are made of thin, fragile bronze, which cannot have been used in war, and the horned helmets must also have been quite unpractical in battle.

But a comparison with the later god Thor is not quite convincing; because where did his twin disappear? In addition, Thor is not known to have worn a horned helmet. But the ax-bearing men with horned helmets are often shown with an erect penis, which brings us to the god Freyr.

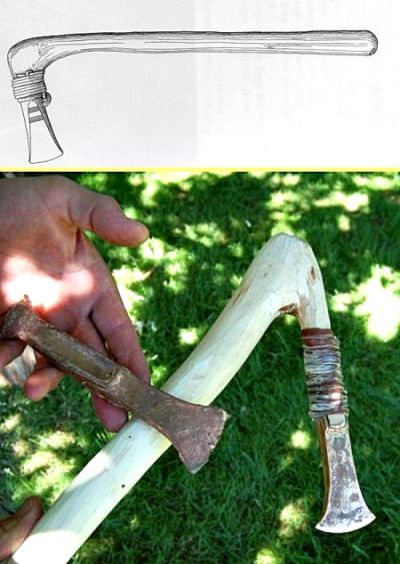

Among the most frequent finds from the Bronze Age are the relatively small labor- and

weapon-axes, called celts. More than 1,000 finds of celts are known from Denmark, and from Sweden more than 1,600.

|

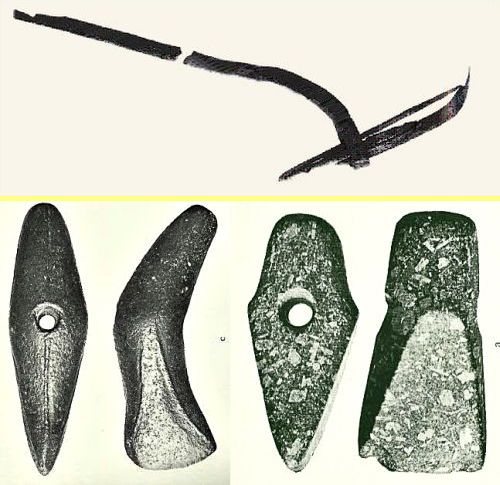

Upper left: Graphic reconstruction of shafted celt. The Wooden handle is inserted into the hollow celt-head, so that celt wedges itself when it is used. However, to be sure the celt head is secured with a cord. One can also imagine that some celt head were shafted in a transverse way like a transverse ax. Remnants of wood found in some celts have shown that the shaft was made of oak.

Lower left: Reconstruction of a shafted pålstav. The wooden handle is fastened with cord in a groove on the pålstav-head. It does not seem to be such a solid connection as the celt, but nevertheless pålstavs seem to have had a higher status than celts. The pålstav has been shaftet by Jess.

Upper right: Ard from the early Bronze Age found at Donneruplund near Vejle.

Lower right: Left - Battle ax of stone from the Bronze Age found on the island of Lolland - front view and side view. Right: - Battle ax of stone from the Bronze Age found in the Abbetved settlement near Roskilde. Note that the casting edge of a bronze weapon is imitated. Indeed, there have been found many traditional flint tools from the Bronze Age, in the form of flint arrowheads, flint scrapers and so on. Not everyone could afford the expensive bronze.

Celt of bronze. It is hollow for shafting and has an eye, where it can be secured with a leash.

Celts are very rarely seen in oak-coffin burials, while they are frequently found separately in wetlands, where they must have been immersed as sacrifices to the gods. This could indicate that they first and foremost were tools and weapons for ordinary peasants, who did not receive such splendid funerals as members of the princely families. Perhaps it also indicates that more ordinary peasants had a veneration for their traditional gods, who lived in the bogs.

As weapons of war, they must have had the same function as the Neolithic battle axes or

battle hammers, namely to seek to crush an opponent's skull.

Evidence suggests, however, that their main function was working ax, as we can observe that the edge often had been hardened and sharpened by hammering. Some conclude that it would not have been necessary if it primarily was a weapon since it does not need to be particularly sharp to crush the skull of an opponent.

Celts from Buskbanke at Voldtofte near Assens. They are incised with images of ships, but they can not be seen in the photo. Photo Asger Kjærgaard.

They are often approximately 4 cm wide and 6 cm. long, but we also known about very small celts.

A pålstav is an open celt, wherein the handle was fixed in a groove instead of a hole. They must have had roughly the same functions as celts, however, they seem to have had a more privileged status since they in several cases are found in rich graves together with swords.

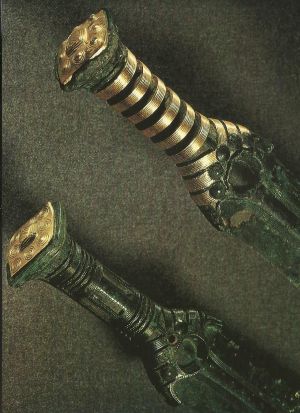

The sword was invented during the Bronze Age, and it was used of men of high status. They are often elaborately decorated. In the Early Bronze Age before 1,300 BC swords were decorated with spirals and circles, and after this time they were only decorated with circles. The scabbards that we know are made of wood, some beautifully decorated and others quite simple. One can wonder why the handles are so narrow; We think, had bronze age men really so small hands?

The answer is probably that the sword was primarily a stabbing weapon, and as a human body has a consistency similar to a piece of fresh pork, it will require some force to stab it into the enemy; therefore the warrior held the sword with his palm behind the upper knob to better push it in.

|

Upper left: Practical Bronze Age swords exhibited in the National Museum.

Lower left: Arrowhead of bronze.

Right: Gold-plated magnificent Bronze Age swords.

Bronze swords were the dominant weapons throughout the Bronze Age. It must be obvious that they mostly must have been a stabbing weapon since bronze is a rather hard and brittle metal. The oldest swords are obviously imported from southern Europe, but very fast Scandinavian smiths developed a true championship in bronze casting.

Bronze swords with beautiful artful grips and gold plating appear very often without a

scratch. They seem only to have been some sort of relics or insignias.

Many swords of a more simple and practical design bear traces of that they have been used in combat; the edge can have small damages, or they have been sharpened to repair such damages.

|

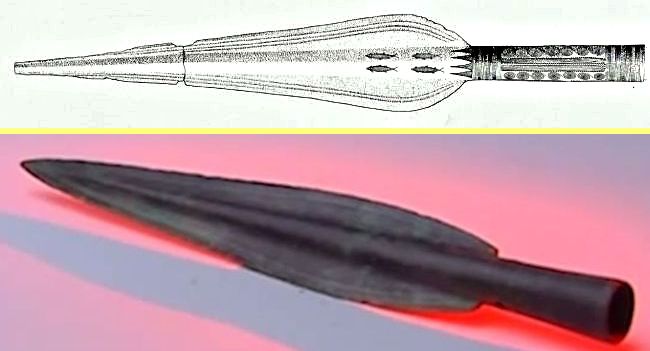

Top: Beautifully decorated bronze spearhead found at Valsømagle near Ringsted.

Bottom: Common practical spearhead from the Bronze Age.

It seems likely that this reflects the organization of society. The splendid swords

belonged to the rich and powerful families and were passed down from one generation to another until they ended up in the mounds. Princes and local kings were surrounded by a group of young sword armed men, who did the actual fighting when the situation demanded.

The ordinary peasants lived around in the villages tending the land. They were armed with celts, stone axes, bow and arrow and the like.

Archaeologists have found bronze arrowheads, but there are many examples of that flint arrowheads and even bone-arrowheads were still in use in the Bronze Age.

All in all different weapons take up much among the finds from the Bronze Age, and many of them have scrapes, showing that they did not have weapons for fun. We must imagine that the political situation was characterized by many small local kings and princes, who intrigued and fought open wars against each other in shifting alliances.

|

Left: A fishing hook of bronze found at Sølagerhuse near Hundested.

Mid: Hairnet from the older woman's grave in Borum Eshøj - The Bronze Age people had the need, the materials and they mastered the technique to manufacture fishing nets, then we must believe that they also did it, even we have not found such nets.

Right: Quantities of fish bones found at Folkemuseet's excavations at Sølagerhuse.

Thanks to the bronze, fish hooks got a somewhat more elegant, and certainly more efficient design than the Stone Age hooks, which were carved from red deer ribs.

In several women's graves from the Bronze Age have been found hairnets; in the production of fishing nets a similar technique is used, which makes it very likely that they had caught fish with nets.

|

The Hjortspring Boat Guild is a group of history fans on the island of Als, who have built a full-scale reconstruction of the Hjortspring Boat. Here it is on sea trial in the waters north of Als in May 2001. It looks like the ships on the rock carvings, especially those from the late Bronze Age.

In connection with Folkemuseet's excavations of several smaller settlements from the Bronze Age in the outskirts of Hundested in 2006, very large amounts of fishbones were found in the layers of refuse. This suggests that during large parts of the Bronze Age people lived in nearly the same way as they had done in both the Stone Age and Neolithic periods, namely mainly from everything from the sea.

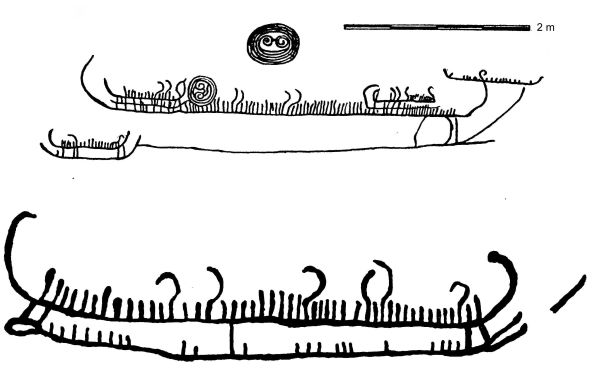

Thousands of petroglyphs depicting ships have been found in southern Scandinavia, but we have never found any remains of such vessels from the Bronze Age. But a 19-meter long boat, which looks like the ships on the carvings, was found in 1921 in Hjortspring Mose on the island of Als; however, originating from the early Iron Age. It was a kind of light war canoe with a weight of only 530 kg. The boat was designed to be paddled by a crew of 24 warriors. Many of the paddle oars and a large steering oar are preserved. We must believe that the Hjortspring boat is an example of a type of ship from the early Iron Age with deep roots in the Bronze Age.

|

A drawing of a ship is incised on a bronze sword found at Rørby near Kalunborg. It is the earliest ship image, which has been found up to now. The sword has been dated to around 1,600 BC.

The ship has a completely even keel, which is extended in bow and stern. The railing frame fore and aft is extended and swung upwards. The crew is drawn as lines with heads

as small dots. The ship may have had 35 to 40 men aboard. The men are sitting in pairs, looking like they paddle in respectively port and starboard.

By counting pixels and men on the photo of respectively the reconstructed Hjortspring boat and the Rørby ship and doing some proportions calculation, the author comes to the result that the Rørby ship had a total length of about 26 meters. Because the Rørby ship is longer, it must also have been wider in order to provide sufficient longitudinal strength, perhaps 2.5 to 3 meters wide. This means that a given cross-section of the boat, say 1.1 meters long, which gives room for two paddlers at the railing, respectively, port and starboard, has been heavier than a corresponding cross-section of the Hjortspring Boat.

This means that the bigger the boat, the more kilos each crew member has to paddle forward.

I remember a remark by Saxo that "Ormen Lange" was taken out of service because it was so heavy to row. ("Ormen Lange" was an ancient ship from the Viking Age, famous, because it was so big).

Perhaps the many very large vessels on the rock carvings are religious motifs, and the

Bronze Age people did really not have such large ships.

The curved sword from Rørby can be dated to around 1.600 BC, and thus it is one of the

oldest known images of ships. The slender ship has high swung bow and stern extensions and keel extensions both fore and aft. Like in the Bronze Age petroglyphs the crew is on board, numbering about 35-40 men, drawn as slashes with heads marked as small dots.

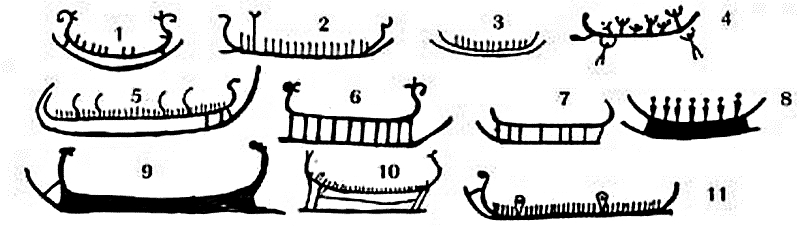

The archaeologist Flemming Kaul has analyzed the many pictures of ships and concluded that there has been a development of ship design through the Bronze Age.

The oldest petroglyphs show ships with keel extension in the aft end as a kind of directional stabilizer. In the fore end, the keel is curved strongly upwards, as was

the case with the later Viking ships. Petroglyphs from about 1,300 BC show an animal head, maybe a horse, and later a bird on the up-swung and back-bent extensions of the railing frame, there is still a keel extension aft. No steering oars are shown.

|

Different types of ships as they appear on the Bronze Age petroglyphs. Many of the ships are decorated with animal heads on the bow extension, some looks like horse heads, other like birds' heads. The many short lines that protrude from the top side of the hull represent most likely crew or raised paddle oars. Some believe that the figures 6 and 7 can be skin boats, like the Greenland konebåd and the Irish Curragh, built of tarred ox-skins pulled over a thin wooden frame. A picture from the 1600's of an Irish curragh shows animal head in the bow. Figures 1, 8, 9, and 3 is similar to wooden boats of a similar type as the Hjortspring Boat. Figure 10 is the rare three-line ship. Figures 4 and 11 could be dugouts - From Axels Fartygs Historia.

It has been suggested that type 7 (see figure), which is found at Lensberg near Tønsberg, originates from 1.100 BC. It has upwardly swung extension of the railing frame, keel extension fore and apparently no animal head or other decoration. Type 6 can be from 900 BC. It is found at Blåholt and Madsebakke. A

type 3 can be from the end of Bronze Age, namely 500 BC since it recalls the Hjortspring Boat.

|

Top: Dugout from the Bronze Age during excavation at Varpelev on Stevns in 1973; it has been carbon-14 dated to around 1,000 BC.

Bottom: Dugout from the Bronze Age during excavation at Vestersø near Lemvig in 1952 -

Note the carved frames, which seek to imitate a plank built boat - it can today

be seen in Lemvig Museum.

Dugout canoes have been used in Denmark from the Stone Age to the age of the Vikings. Because of their poor stability, it must be assumed that they generally have been operating in rivers, lakes and inland waters.

In Denmark have been found two dugouts from the Bronze Age, namely the boat from Vestersø at Lemvig and the one from Varpelev on Stevns. They have both the typical flat bottom, the characteristic carved frames and the carved stern, which is common on Central European dugouts from the Bronze Age.

Viksbåten is a plank-built wooden boat, which has been found in a burial mound in Sweden and is exhibited in Söderby-Karl's hembygds och Fornminnesförening - Vid Erikskulle. - to my knowledge, it is a boat from the Bronze Age. In England have also been found plank-built wooden boats from the Bronze Age, namely in Ferriby at the Humber River and at Dover. But none of them are so light and elegant as the Hjortspring Boat.

The flat bottom gave the Bronze Age dugouts a slightly improved stability compared to the Stone Age dugouts, which were totally round in the bottom.

The dugout from Varpelev is built of an uniquely long and straight oak trunk. It has carved frames and stern, which is typical for the dugouts of the time. As many European dugouts from the Bronze Age, it is the very long, about 14 meters; that should be related to stone-age dugouts, which were almost 10 meters long or shorter.

It must be recognized that a 14-meter dugout found on Stevns is bound to have sailed on Øresund, as there are no rivers or lakes in this area, which can justify such a large boat.

The dugout from Vestersø is also made of oak, but unusual for the bronze age it is rather short, namely only 6.2 meters. It has 4 carved frames, each 4 cm high. The wall thickness of the sides is 3.5 cm and of the bottom 8-10 cm.

|

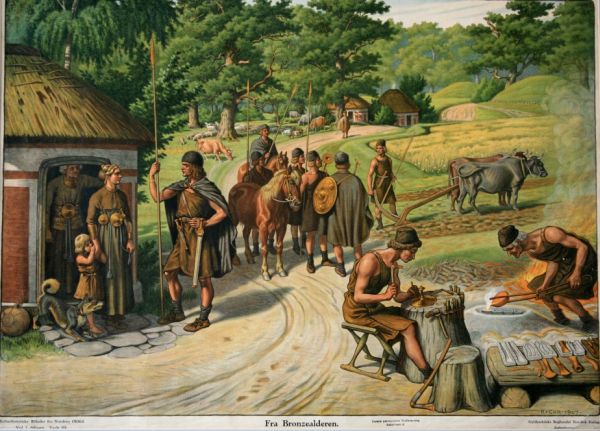

A scene from the Bronze Age painted by Rasmus Christiansen in 1925. One can argue against the Bronze shield, which one of the men is carrying on the back. Many believe that these round Bronze shields were impractical in war and were used only in religious ceremonies. In addition, excavations have suggested that houses were characterized by relatively low side walls, a dominant thatched roof, entrance at the end of the house and interior support-posts. The house type in the picture is reconstructed after painted urns found at Stora Hammar near Skanør in Scania and many other places not only in Scandinavia but also far down into Europe.

In South Jylland archaeological excavations have shown that houses from the last part of Neolithic are found only in locations, where there also have been found house sites or burial sites from early Bronze Age, indicating continuity between Neolithic and Bronze Age. A large part of the Bronze Age people has likely been descendants of the Stone Age farmers.

Because of the unique preservation conditions several very well preserved burials from the Early Bronze Age have been found during the last hundred years. Totally a half hundred burials in oak coffins have been excavated, however, many by inexperienced people, which caused that objects and information have been lost. But nearly a dozen oak coffins have survived with their content.

Evidence from the burials suggests that the Bronze Age people were some slender fair-haired types similar to many modern Danish types in stature. They were slightly higher than the old Stone Age hunters and peasants, but not so strongly built. Some have calculated from the found skeletal material that the average height of men was 173 cm. and of women 164 cm.

They dressed in suits of woven wool of different design. The men shaved and used round topped floss-caps.

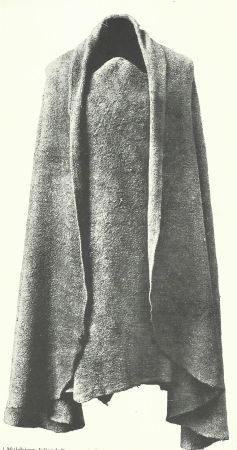

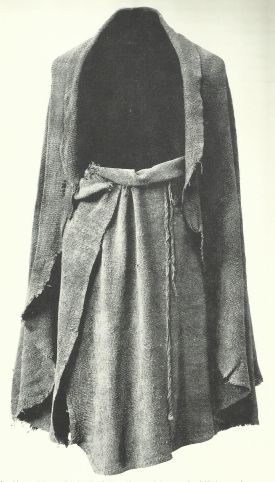

Male clothing from an oak coffin in Tvillinghøj at Mulbjerg. The inner coat has probably been held up by a leather belt and maybe two small leather straps over the shoulders. The jacket has after all accounts been worn symmetrically as shown and held up by two bronze shackle pins.

We may wonder where the old hunters and peasants had gone; but it was probably so that it was only the Bronze Age upper class that got part in the splendid funerals, and the hunters and Stone Age peasants' descendants might not belong to this group. From the Bronze Age, only one person has been found who may be regarded as one of the old hunters'

descendants; That is the older woman from Borum Eshøj, who was a long-skulled Cro Magnon type. Furthermore, some believe that the Skrydstrup girl was long-skulled and thus could have had some of the hunters' blood in her veins.

In Tvillinghøj at Muldbjerg near Ringkøbing an oak coffin was excavated in 1883. The man in the coffin had been 180 cm. tall. He was wearing a knee-long kilt of wool held up by a

leather belt, and he also wore a wool jacket. On his head, he had a round-topped floss-cap. Like all men from the Bronze Age, he was clean shaved. He had shoulder-long hair with center parting. At his right hand was a bronze sword in a decorated wooden scabbard. He had his horn comb and bronze razor with him in the grave. The coffin is dated to 1365 BC.

In Trindhøj at Vester Vamdrup west of Kolding a man was found, wrapped in a cowhide, with his woolen cloak over him. On his head, he wore a floss-cap. He had got his sword in a carved wooden scabbard, a comb of horn and his bronze razor with him in the grave. Of the skeleton was nothing left, but his blond hair was preserved.

In Borum Eshøj at Aarhus, three unique oak-coffin burials from about 1.350 BC were found around 1870. They contained the bodies of two men and a woman clothed with some of the best-preserved bronze age costumes, which have been found until now. There were also many grave goods in the coffins.

|

Top: The old man from Borum Eshøj.

Bottom: The young man from Borum Eshøj.

Borum Eshøjs central tomb contained the body of a lightly built 50 to 60-year-old man, approximately 170 cm tall, with blond hair and manicured nails. He lay stretched out on a cowhide. The man was dressed in a kilt of wool fastened with a belt around the waist and a round-topped hat, and the corpse was covered by a round cut woolen cloak.

The second of the oak coffins from Borum Eshøj contained the body of a young man, who was about twenty years old when he died. His body was very well preserved at the time of the excavation; muscles and other soft tissue still connected bones with each other. He has been around 166 cm. tall, lightly built and with round skull. He wore a kind of kilt of woven wool fastened with a leather belt and a cape. The remains of his pubic hair were still sticking on the inside of the kilt, suggesting that he had not been wearing anything under his kilt. On his head he wore a round-topped hat, and by his side lay a sword-scabbard of wood, which only contained a short Bronze dagger. Over his right shoulder was a wide leather strap, which had carried the scabbard. It is possible that he also had a pair of leather shoes on. Like most other inhabitants of the mounds, he had got a comb in his coffin. A well-groomed appearance must have been very important in the Bronze Age. A big cloak of wool had been placed over him.

|

Left: The female garment from Borum Eshøj is somewhat more decent than the Egtved girl's. It consists of a blouse, skirt, belt and hairnet.

Right: The old man in Borum Eshøj was dressed in a kind of kilt and a cloak of woven

wool.

The third burial in Borum Eshøj was a woman, who had been between 50 and 60 years old when she died. Her hair was long, braided and light blond. She was strongly built and not

very tall, about 156 cm. Traces on her bones revealed strong muscles. She had a long skull with deep eye sockets. She may have been a descendant of the ancient hunters, we may think. Her suit is very well preserved and consists of a rectangular piece of cloth sewn

up of several parts, blouse, hairnet, cap and two belts, all made from wool. Furthermore, there were found a bronze belt plate, a neck ring, bangles, spiral finger rings, a clothespin, a clay pot, a wooden box, a bronze dagger, and a horn comb.

The best known Bronze Age burial is the Egtved girl's grave at Egtved near Vejle, which

was excavated in 1921.

|

Top left: Shortly after the excavation conservator Gustav Rosenberg drew this reconstruction of the Egtved Girl. It is based on observations made during the excavation and will probably come the real conditions around her dress quite near.

Top right: Female figure in bronze found at Grevensvænge near Næstved. She makes a backward bridge or somersaults. She is only wearing a neck ring and the same kind of cord skirt as the Egtved Girl, however, a little shorter.

Bottom left: Female figure of bronze found at Fårdal near Viborg. She offers her breast and is dressed in the same type of cord skirt as the Egtved girl - and nothing else.

Bottom right Rock carving of a right-sailing vessel at Sotetorp near Tanum, Bohuslen. An acrobat makes somersaults over the heads of the crew.

She was between 16 and 18 years old when she died a summer day around 1,400 BC. That it precisely was a summer day, one can conclude from that a summer flower, a yarrow, lay at her left knee. During the time of the excavation, all the girl's skin was well preserved, while bones and internal organs were completely gone. She was probably buried in her ordinary summer dress, which was a blouse with half-length sleeves and a knee long cord skirt.

The Egtved girl's hairstyle drawn by Claus Deleuran.

The girl from the Egtved was 160 cm. tall and fairly slim with a waist size of 60 cm. Her hair was blond, cut short and loose.

In the Bronze Age, it was quite hot in the summer, and it is not unlikely that a short

blouse and a cord skirt has been regular summer clothing for young girls of good

family.

Some have objected that it is not likely that ordinary young women have been so provocatively dressed, and the airy cord skirt and short blouse were characteristics of

special young women with acrobatic duties in connection with religious ceremonies. A

bronze figure, which was found at Grevensvænge in 1700, imagines precisely a girl in

cord skirt and nothing else, who makes a backward bridge or somersaults. Several petroglyphs show figures that make somersaults over the heads of the crew of a ship. In this case, the cause of death for the Egtved Girl could have been an unfortunate jump.

The Skrydstrup Girl with golden earrings and elaborately arranged hair.

At Skrydstrup near Vojens, another burial from the Bronze Age was found in 1935. The skeleton was only partially preserved. Also this time it was a young woman; she was about 18 years old when she died. She was laid to rest on a layer of forest chervil, from which one can conclude that she too was buried in the summer. She has been around 170 cm. tall and lightly built. Her hair was reddish and arranged in an elaborate hairstyle. She had a narrow face and long eyelashes. It is estimated that she had a long skull. She was more decent dressed than the Egtved Girl, as she was wearing a large skirt that covered the whole lower body and a blouse with half-length sleeves of similar cut as the Egtved Girl's. She was wearing a sort of leather moccasins and was covered by two woolen blankets.

In Guldhøj at Vester Vamdrup southwest of Kolding the body of a man was found that was buried with his pålstav, bronze dagger and folding chair with an otter-fur seat. There were no remains of the skeleton, but part of his blonde hair was left.

In Lille Dragshøj at Højrup near Haderslev the body of a man, wrapped in an animal skin, was found in 1859. A few parts of the soft tissues but nothing of the skeleton were preserved. His now dark, but originally blonde hair still existed. He had got his scabbard, but not his sword with him in the grave. Instead, a dagger was stuck in the scabbard as a substitute.

Toppehøj at Bjolderup near Aabenraa was opened in 1827, and the body of a man in an oak coffin was found. He had got all his weapons with him in death, which were his sword and pålstav. The skeleton was not preserved, but a lock of his blond hair was still there.

In an oak coffin unearthed at Nybøl near Sønderborg was found a fairly well-preserved skeleton of a pretty lightly built man with round skull, who has been 1.75 m. tall.

In an oak coffin grave at Viksø near Hillerød an incomplete skull and a thigh bone were found from a middle-aged round-skulled man, who has been around 1.71 meters tall.

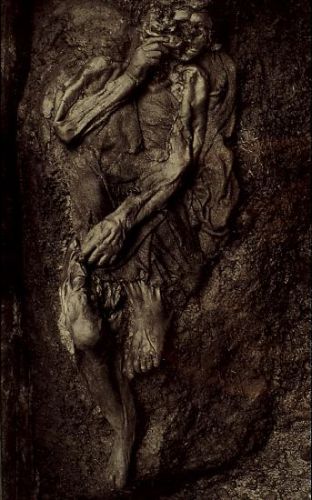

The woman from Borremose is stored in the National Museum, but she is not on display. Photo tollundmanden.dk.

In Denmark, southern Sweden, northern Germany, Holland, England and Ireland have been found more than 150 bodies buried in bogs. Carbon-14 analysis has shown that most are from the end of the Bronze Age and the oldest Iron Age.

One of the oldest known bog bodies in Denmark is a bronze age woman, who was found in 1948 in Borremose near Aars in Himmerland. She was between 19 and 35 years old when she died around 700 BC. She was pretty fat. She was found lying on her belly in the bog, naked but covered with a wool skirt. One leg was pulled up under her. The probable cause of death must have been a violent blow with a club to the head. Furthermore, she had the whole face crushed by another powerful blow. Before or after death, she had been scalped, as the skin of the top of her head and the hair only stuck on the head with a few meat shreds.

No one knows, why she was subjected to a such a brutal and humiliating treatment, but many guess that she was an unfaithful woman, because through the Middle Ages, and probably earlier, cutting the hair have been unfaithful women's punishment.

The man from Borremose with the rope around his neck - Photo tollundmanden.dk.

In his book "Germania", Tacitus has some remarks about this, although he did write several hundred years later. He wrote about the Germans: "The size of the population taken into consideration there are very few cases of marital infidelity. The penalty for this falls immediately, and its execution is left to the husband. He cuts his wife's hair and strips her naked in relatives' presence. Then he chases her away from the home and drives her through the village with a whip." She was not scalped in the Iron Age, but maybe the habits had softened since the Bronze Age.

In the same bog have been found two other corpses from the transition period between the Bronze and Iron Ages. One was a man, who had been strangled with a rope that still stuck on his neck. He, too, was naked. As the woman, he had furthermore got the back of the head crushed with a violent blow that definitely had opened the skull. His right thighbone was broken. A few fur coats were laid at his feet.

The man was rather small in stature, namely 1.55 meters tall. The left hand was particularly well preserved; it was very well groomed and showed no trace of hard physical work. The feet were also very well groomed with carefully cut nails. Examination of

his stomach content showed that he just before his death had eaten a kind of porridge cooked on various weed seeds.

It was not society's dreg, which ended up in the bog; they were well-fed and well-groomed persons.

It is an indisputable fact that we in Scandinavia today speak an Indo-European

language, which has many similarities with other Indo-European languages, which are almost all European and Indian languages.

Proposals for localization of the original Indo-European homeland.

It is highly probable that such a common original language in a distant past may

have developed within a limited area, which is the mysterious original Indo-

European homeland. Nobody knows where it was, but there is no shortage of theories. The most widespread theory, the Cuban theory, tells us that it was in the area northwest of the Caspian sea, which in the past was covered with scattered forest. Others believe that the original homeland was in southern Ukraine, in the Danube valley, on the Balkan Peninsula, in Scandinavia or in Anatolia in Asia Minor. However, according to the Androvno theory, it was in present Uzbekistan. Some even believe that the original Indo-European homeland was located as far east as in the modern Chinese Gansu province.

Therefore, if we exclude the theory that the Indo-European original homeland was in Scandinavia, we must face that an immigration has taken place at one time or another, only we do not know when. It may have been at the time of introduction of agriculture in the Neolithic period, it could be at the Single Grave people's arrival to the heathland of Jylland, at beginning of Bronze Age or at the start of the Late Bronze Age. We do not know, but at the start of the Bronze Age is a qualified guess

It does not necessarily mean that the descendants of the ancient hunters and Neolithic farmers were wiped out or displaced, but in a period they probably did not belong to the upper class of society.

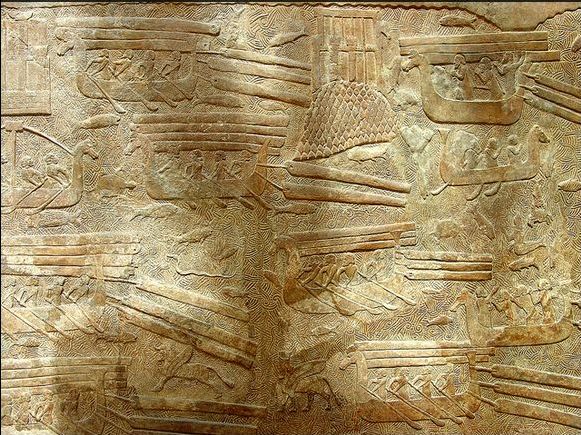

|

Relief from Sargon II's palace at Dur-Sharrukin now Khorsabad showing Phoenician ships

with horse stern ornaments that bring cedar from Lebanon - Louvre Museum. - Many Bronze Age petroglyphs show ships with horse stern ornaments. Bard's poems from the later Viking period mention ships as sea horses, although horse-heads have been replaced with dragon heads. Some bring forward that the interest in horses is an Indo-European feature. However, the Phoenicians were Semitic-speaking people of unknown origin.

We can not know for sure if the Bronze Age people were Indo-Europeans or not.

We can not talk to them, and they left no written reports. Also, no more civilized neighboring peoples have left stories about them. However, some believe that the Phaeacians in Homer's epic, Odysseus, was the Scandinavian Bronze Age people.

An Indo-European immigration that introduced a new language, must have had a very large

cultural influence in other areas, such as religion. It is not unreasonable to search for common Indo-European gods and religious ideas in rock carvings and incised images on bronze objects.

Various researchers have some ideas about what kind of culture and religion, one can expect to find in an Indo-European people. There will be a god associated with the sun, a

god of thunder, an underworld, a prediction of a devastating final battle, a certain dualism personified in twin gods. Horses are given great significance, possibly they sacrifice horses to the gods. Society will often be divided into three castes, something similar to the proposal of Plato in "The State". Namely, in the group of rulers, who are princes and high priests, the guardians, who are warriors and soldiers, and finally the ordinary people who take care of their work.

And some of these traits are believed to be recognized in the findings, drawings on bronze objects and the rock carvings. In addition, contemporary neighboring people further south in Europe are clearly identified as Indo-Europeans, because of their language, and therefore it is concluded that it was Nordic Bronze Age people probably also.

|

Axels Fartygshistoria Axel's History of Ships. Hjortspringbåden Per Nielsen. Hjortspringbådens Laug Geoviden - Geologi og Geografi nr. 1 2007 Geocenter København (pdf). The Odysse by Homer - Book VIII Translated by Samuel Butler. The Odyssey by Homer - Book XIII Translated by Samuel Butler. Odysseus' og Menelaos' lange hjemrejser fra Den Trojanske Krig Verasir af Flemming Rickfors Bronzealderskibets weblog Fra ide til bronzealdercenter. Helleristningsguide - Bilder i berg i Norden Arild Hauge. Fyns fantastiske fyrster forsvandt ud i det blå Videnskab dk. Ældre Edda - fuld tekst Internet Archive. Folkeviser - Elverhøj Kalliope Digtarkiv. "Helleristninger - billeder fra Bornholms bronzealder" - Bornholms Museum wormanium 2005. "Bronzealderens Religion" - Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab - København 2004, af Flemming Kaul. "I Østen stiger solen op" (kronik i Skalk 1999 nr. 5, s. 20-30) af Flemming Kaul. "Solsymbolet" (Skalk 2000 nr. 6, s. 28-31) af Flemming Kaul. "Åndeligt opbrud" (kronik i Skalk 2003 nr. 6, s. 20-27) af Flemming Kaul. "In Search of the Indo-europeans - Language, Archaeology and Myth" af J.P. Mallory - Thames and Hudson 1996. "Danmarks Oltid" 2. Udgave bind 2 Bronzealderen - Johannes Brøndsted. Gyldendal 1960 |

| To top |