|

Home DH-Debate 41. Erik Menved 43. The Kingless Period |

For 700 years, Christoffer 2 has been the historian's favorite prügelknabe. He was the irresponsible king that was the reason why Denmark was close to disintegrating and disappearing into the myriad of German principalities in the 1330's.

Portrait of Christoffer 2. in detail of his tombstone in Sorø Church. There must be portrait likeness, as the bronze statue was created quite a few years after his death. Photo Mariusz Pazdziora Wikipedia.

But in reality, he had taken on an impossible task. From the first day of his reign he was handicapped, having to personally take over a huge debt from his brother, Erik Menved.

King Erik had pursued a very ambitious and aggressive foreign policy in both Sweden and Northern Germany. In this connection he had used mercenaries on a large scale. He financed them with borrowed funds so that in return for the money he gave the creditors the so-called pawn fiefs, which means that each creditor was given a part of Denmark - for example Fyn or Scania - and was given the right to collect all the taxes, fines and fees, which the king was otherwise entitled to collect in these parts of the country until the loan was redeemed.

At Erik Menved's death in 1319 , large areas of Denmark, perhaps 35-40%, were laid out as pawn fiefs or otherwise prevented from contributing to the royal revenue. The whole of Funen was mortgaged to the Holsten counts, Scania was mortgaged to Marsk Ludvig Albrechtsen, the island of ærø was mortgaged to the Margrave of Brandenburg and so on.

Parts of Denmark that were not available to Christoffer 2 at his accession to the throne in 1320, Scania and the islands of Fyn, ærø, Lolland, Falster, Møn, and Samsø were pawn fiefs. South-Jutland and North-Halland were in practice independent duchies outside the king's influence. In addition, much estates of the crown, scattered throughout the country, was also reserved as security for debt. Photo Bent Hansen.

At the same time as Christoffer personally had to take over all this enormous debt as a precondition of being elected as a king, he had to sign a hand-binding contract, which forbade him to impose new taxes, yes even reduced the royal revenue in the areas which at this time was still not pawn fiefs - and thereby in practice made it impossible for him to redeem the many and large pawn fiefs.

|

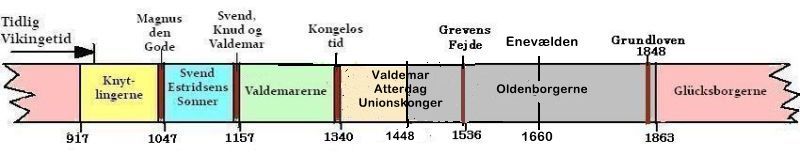

Denmark's history divided into Royal Dynasties. However, all the kings - except Magnus the Good - descend from "Hardegon, son of a certain Sven", who conquered a large part of Jutland around 917 as told by Adam of Bremen in his section on Bishop Hoger. The line of kings and times of war and peace are the backbone of history - not that stories about culture and ordinary people's living conditions are not important and interesting - but without the line of kings, history can easily become a kind of relatively unstructured conversation about aspects of Danish history that pedagogically are not easely fixed time. It improves overview to divide the royal line - and thus Danish history - into manageable sections.

The Knytlinge dynasty got its name from a Hardecnudth, most likely son of Sven. He is also called Knud 1. and was with great certainty the father of Gorm the Old, as narrated by Adam of Bremen under Bishop Unni.

Magnus the Good, who became king in 1047, was the son of the saint king Olav of Norway; his reign forms a period of transition to the time of Svend Estridsen and his sons and grandsons.

The rival kings, Svend, Knud and Valdemar, from 1146 to 1157, all descended from Sweyn Estridsson; their time makes up an interregnum to the time of the Valdemars.

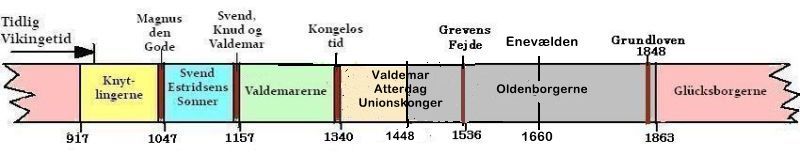

Many historians, probably most, only count Valdemar the Great and his sons, Knud the Sixth and Valdemar the Victorious to the Valdemars. But no one can patent such a definition, and it seems to the author advantageous also to include their less successful descendants - who are Erik Ploughpenning, Abel, Christoffer 1, Erik Klipping, Erik Menved and Christoffer 2. who was the last king before the kingless time from 1340.

Valdemar Atterdag was not king of the Kalmar Union, but his grandson, Olaf, was, and his daughter, Margrete 1. became queen of the Scandinavian Union. One can say - with a little good will - that Valdemar Atterdag recreated Denmark and thus the possibility of the Kalmar Union with Norway and Sweden.

The first Oldenburg kings were only Union kings for short periods.

The Civil War, the Count's Feud, in 1534-36 was a landmark turning point in Denmark's history. As a consequence of the Lutheran Reformation, which took place at the same time, the kings were able to confiscate the third of Denmark's agricultural land that belonged to the church. This fabulous wealth made it possible for them to subdue Denmark's old nobility and after some time to establish the autocracy, which became one of the most important causes for Denmark's continued historical decline.

In 1848, a democratic constitution was implemented without civil war or other violent events.

The Oldenburg royal family died out in 1863 with the childless Frederik 7. After that, Christian 9. of Glücksborg was appointed king.

Some Danish nobles allied in 1325 with the Holsten counts and started a revolt against their king, which quickly spread to the whole country. King Christoffer, Queen Eufemia and their youngest son, Valdemar, had to flee to Northern Germany.

Already 1326 Count Gerhard of Holsten had both Jutland and Fyn in his power. The Holstenias and the rebellious nobles then appointed the only 11-year-old Duke Valdemar of South-Jutland king. Due to his young age, his maternal uncle, Count Gerhard of Holsten-Rendsborg - called the "The Bald Count" - was at the same time appointed his guardian and head of state.

The Valdemars. It is customary only to attribute Valdemar the Great, Canute the Sixth and Valdemar the Victorious to the Valdemars. But thereby their less successful descendants become pedagogically homeless, even though they are true descendants after the first and more famous Valdemars, and they are not separated from these by any natural interregnum. Therefore, I would suggest that the whole group from Valdemar the Great to the kingless time to be called the Valdemars.

Erik Ploughpenning, Abel and Christoffer were sons of Valdemar the Victorious and they succeeded each other as kings. Abel killed his brother, Erik, and had his body immersed in the fjord, Slien. However, 24 knights swore he was innocent, and therefore he was elected king anyway. However, only a short time later, he was killed in battle during a campaign against the Frisians, and then his younger brother, Christoffer, was chosen as his successor, and the deceased Abel's eldest son was thereby bypassed. In the following decades, this led to a long-standing rivalry between the descendants of Abel and Christoffer, respectively, and that contributed to the historical division of the original Denmark into the kingdom and the duchies.

Christoffer's son, Erik, who was later bynamed Klipping, only 11 years old became king with his dynamic mother, Margrete Sambiria, as a guardian. The great men limited his power with a hand-binding contract at Nyborg Castle, which among other things decided that the meeting of the king and great men, which was later called the Danehof, should be the country's highest court.

In addition, it was ruled that the king's court could only deal with cases that had previously been presented to another court, and that it could only impose standard fines. Erik Klipping was killed in Finderup Lade near Viborg with 56 fatal wounds and this murder is still one of the great mysteries in Danish history. His son, Erik Menved, tried to make increased influence in northern Germany by holding some magnificent - but certainly expensive - knight tournaments. He was succeeded by his brother, Christoffer 2., who had to take over his large debts, while at the same time the possibilities of increasing the royal revenue by increased taxes were blocked by a hand-binding contract. When he died in 1332, no new Danish king was elected, and for a period the country was thus without a king.

In 1329, the creditors divided the provinces of Denmark among themselves, which triggered a new revolt based in Jutland. Supported by another of Denmark's great creditors, Johann the Mild of Holsten-Plön, the rebels called Christoffer home and recognized him again as king - but with extremely limited means to exercise royal authority.

Perhaps in 1330 there was a war between Denmark's two largest creditors, namely Count Gerhard and Count Johan den Mild. Christoffer took Johan's side, but in the battle of Kropp Hede a little north of Danevirke in 1331 Gerhard won.

The rest of his reign - and his life - Christoffer spent in rather scarce economic circumstances considering he was king. He died in 1332 in his modest home on the island of Lolland.

Christoffer had many good qualities, which under more favorable circumstances could have made him a good king.

Christoffer 2. of Denmark, detail from tapestry at Kronborg Castle. The wall tapestry at Kronborg were made in Helsingør in 1584, almost 300 years after Christoffer's lifetime. They have not known him, but it is clear that the weavers have worked with his grave monument in Sorø as a template. It probably looks pretty good like him. Foto: Orf3us Wikipedia.

He was, according to all that is said, 100% committed to his task as king, and thereby he probably differed from his father, Erik Klipping.

He was not afraid to address the issues and make decisions. They could turn out to be wrong, but that's the case with management decisions under uncertainty. One should be happy if most turn out to be reasonably right.

But Christoffer never really became popular. The Danes may have had positive expectations of him in connection with his accession to the throne in 1320. The simultaneous hand-binding contract - although it was very unrealistic - reveals a mood of new beginning after Erik Menved's heavy taxes and foreign adventures. One may have imagined that now everything was getting better, the exiles could return to their fathers' homes, and they had chosen a completely new king.

But the enormous debt that Erik Menved had created could not be removed by majority decisions. It had now been laid on the shoulders of Christoffer, and he had to do something - which did not harmonize with the unrealistic hand-binding contract - in order to generate sufficient income for the crown.

Fresco from around 1390 in Tirsted Church, showing Jesus, which is presented for King Herodes. Photo kalkmalerier.dk.

This may have created the disappointed expectations expressed in a the contemporary Danish Chronicle: "He practiced no justice, but rather ruled like a tyrant, truth was not in his mouth, and he was unbridled in every way, on the peasants he imposed harsh taxes, and the noblemen he ruthlessly imprisoned or chased out of the country."

One thing that must have especially contributed to the opposition to him was his longing for international fame, which his brother had also had - in fact very similar to modern politicians.

Historian Palle Lauring describes Erik Menved's knight gathering at Rostock in 1311 as a really very extravagant event that lasted four weeks with artificial fountains with red and white wine, plentiful tables with food that everyone could supply from and free oats for thousands of horses. The author thinks he has it from Arild Huitfelt, who wrote around 1600.

The contemporary Lübeck chronicle also reports that it was a very extravagant event, though without fountains with red and white wine, but mentions that it only lasted for two days.

The Sjælland Chronicle, the Danish translation of Ryd Monastery Annals and the Ribe Annals agree that there was a drought, misgrowth and inflation time in Denmark in 1311.

Knight tournament during Danehof festival in Nyborg in 2014. Foto: Nyborg Slot.

When the story of King Erik's excesses at Rostock in 1311 has grown to such an extent in the course of 300 years, it must be because the Danes had to a very large extent identified it as the characteristic of Erik Menved. Imagine that in a year of misgrowth and inflation in the country, their king threw taxpayers money away in the most unheard way in order to become popular in the international world.

But Christoffer demonstrated the same longing for international fame as his brother, which must have challenged public sentiment. As soon as he became king, he formed a coalition with the North German princes. He promised the Margrave of Brandenburg, the emperor's son, an astronomical sum of money as a dowry for his daughter, Margrete, and he surrounded himself with German knights and mercenaries.

By all accounts, Christoffer was somewhat vain and impulsive and therefore easy to tease. Upon his return in 1329, he was told that Copenhagen would open its gates to him. But his half-brother, count Johan, got word of this and sent a group in advance, which pretended to be the king's men. They hoisted the Holsten banner with the "nettle leaf" over the castle. This made Christoffer very angry. Johan took it easy, it must have been a joke, and for some time afterwards he referred to Christoffer only as "the former king", which must have further annoyed him.

Christoffer was only one or two years younger than Erik Menved. Most of his active life he stood in the shadow of his royal brother entitled Duke.

As early as the spring of 1294, the 18-year-old Duke Christoffer made a name for himself of determination and drive by capturing Archbishop Jens Grand on behalf of his brother, the king. Unimpressed, he led the holy man in gallop through Scania and on to Søborg Castle in North Sjælland, where he was thrown into the castle's deepest dungeon.

In the case files concerning Erik Menved's case against Jens Grand before the Pope's court in 1297 it is mentioned that the brothers Erik and Christoffer stood together as exponents of the threatened Danish royal power, which they had inherited from their father, and which they now fought to preserve against the attacks directed against it.

In 1300, at the age of 24, Christoffer married Eufemia of Pomerania, who was 15 years old at the time of the wedding.

However, in 1302 or 1304, the Margrave of Brandenburg in a letter to the town of Lübeck could suggest that it was quite true that the two brothers were in hateful conflict with each other.

Side decorations on Christoffer 2's tomb in Sorø Church, which is a bronze casting work from Lübeck from 1776-77. To the left is Samson overthrowing the Temple, then Samson in Dalila's lap. Then David's son, Absalom, who goes in to his father's concubines, and on the far right, the Greek philosopher Aristotle, who, like an old man, was charmed by the harlot Phyllis, who uses him as a riding horse. Foto: Jens-Jørgen Frimand.

According to a continuation of Saxo's Danish Chronicle written down by the monk Thomas Gheysmer after an earlier chronicle from Valdemar Atterdag's time - Duke Christoffer sought connection with the Swedish Dukes and King Hâkon of Norway immediately after he had been appointed Duke of South-Halland and Samsø in 1307.

In this connection he should - still according to the chronicle written down by Thomas Gheysmer - have clearly stated that it was his intention with their help to become king of Denmark instead of Erik Menved.

If this is true, it is clearly high treason, as his brother and king, Erik Menved, had allied with the brother of the Swedish dukes, the Swedish king, Birger Magnusson, with a double brother-in-law relation and several times provided him with military assistance against his brothers, the dukes mentioned above.

It must probably mean that Duke Christoffer have already thought that his royal brother had gone on a completely wrong track and he thought he could do better.

Kärnan in Helsingborg was built by Erik Menved around 1315, where it replaced an older and smaller tower. The tower was originally surrounded by a ring wall. Dendro-dating of the original wooden beams shows that the floor timber in the two lowest floors was felled in the years 1315-1317. From the royal letters it can be seen that the king often stayed in Helsingborg. It was also here that he in 1296 he celebrated his wedding. Foto: Wikipedia.

Some years later, in 1311-1313, King Erik could find his brother on the side of the Jutland rebels.

Some historians state that the revolt, which probably took place in 1312-1313, was triggered by the extra taxes that Erik Menved imposed to finance the very expensive - but failed campaigns in Sweden in 1309, during which several Danish nobles left the army prematurely and traveled home.

Sjælland Krønike, the Danish translation of Ryd Monastery Annals and Ribe Annals agree that there was drought, misgrowth and inflation time in Denmark in 1311.

1311 was also the year when King Erik held his widely famous but also very expensive knight tournament and celebration outside Rostock, which was probably rumored in Jutland.

The historian Palle Lauring tells that on this occasion King Erik knighted his brother along with countless others.

But Duke Christoffer must have had a leading role in the uprising in 1313 for the Essenbæk Chronicle found occasion to write for the year 1315: "King and Duke have become friends." Which suggests that they were not before. This is confirmed by a settlement document issued in Nyborg on 14. December 1315. Duke Christoffer was then 39 years old.

Detail of side decoration on Christoffer 2's tombstone in Sorø Church, which shows the Greek philosopher Aristotle, who as an old man was seduced by the prostitute Phyllis, who used him as a riding horse. Foto: Jens-Jørgen Frimand.

However, the friendship did not last long. Late in the year 1316 - while the war against Brandenburg raged - Duke Christoffer invaded the island of Fyn, looted Svendborg and fought against King Erik's bailiff on Fyn, Jakob Flep.

Together with the exiled archbishop, Esger Juul, Christoffer's own commander in Halland, the Sjælland nobleman Eskil Krage, invaded Scania and burned down the castle Örkelljunga.

In 1317 a peace treaty was made between King Erik and the Margrave of Brandenburg in Vordingborg, apparently based on a strong Danish military position. Amnesty was granted to Duke Christoffer and other Danish refugees who had fought with him against Erik Menved.

On 25 January 1320, Duke Christoffer signed a Hand-binding Contract in Viborg, and was then hailed as king on the county tings.

Christoffer was the first king to sign a hand-binding contract as a precondition of becoming king. Erik Klipping also signed a hand-binding contract, but it was in the middle of his reign and he did it voluntarily - so to speak for the sake of good cooperation.

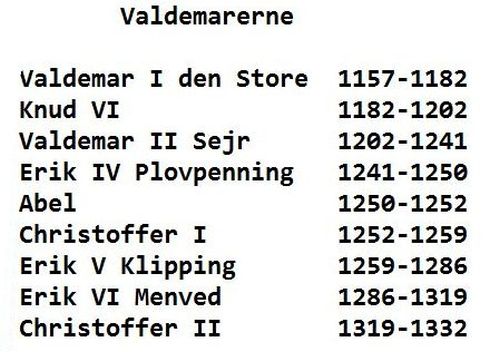

David is anointed king in "The Morgan Leaf", The Winchester Bible from around 1200 it is said. Photo Smarthistory.

The very existence of such hand-binding contract confirms that the Danish Electoral Kingdom was real.

It was in the spirit of the hand-binding contract that friends and foes now had to reach out for reconciliation. It manifests a mood of new beginning. All the refugees were allowed to return home - except for the former drost, Niels Olufsen Bildt.

Most of the outlaws from 1287 had died, but their children and grandchildren could now come home and take over their fathers' estates, which had meanwhile been in the king's possession. This was obviously another cut in the newly elected king's fortune and income.

The the hand-binding contract is similar to modern human rights in that it says nothing about the duties of clergy, nobles, peasants and citizens, but only talks about their rights. It is understood that it is the government, in this case the king, who had a duty to fulfill and respect these rights.

We must believe that the duties of the people were defined in the ancient laws and that they were generally obliged to obey their king and his representatives - as soldiers have a duty to obey their officers.

The the hand-binding contract contains 37 paragraphs, all of which describe what the king should do and what he should not do, including what rights restrict him in the exercise of his royal duties for the good of the people and the kingdom.

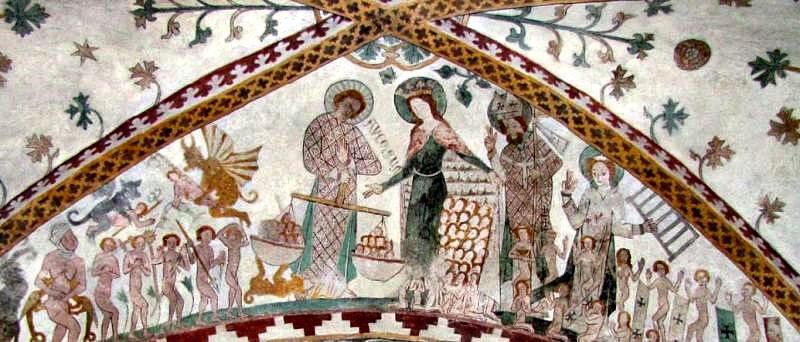

Fresco in Birkerød church north of Copenhagen from 1325‑50, which shows the soul migration. The archangel Michael weighs the dead with a bismer scale. To the left, a devil tries to weigh down the scales so that the souls end up in Hell. But to the right is the merciful Maria, who simply by placing two fingers on the scale can make the weight tip. Maria lifts up her cloak and shows that there is a large crowd of praying souls hiding. Behind her stands sct. Nicolaus to whom the church is consecrated. Photo TrapDanmark.

An absolutely decisive provision in the hand-binding contract was that the new king should be liable for the entire debts of the former king: Furthermore that he must pay in full all verifiable and with probable proofs made likely debt which the now deceased king had to the inhabitants of the kingdom, and the sureties agreed for him must be complied with until it is paid in full."

It is noticeable that the first 10 paragraphs in mainly define what the king may not do in relation to bishops, priests and monks. These are remarkable things. If Jacob Erlandsen or Jens Grand had experienced this, they would have felt that it was Christmas Eve and they had all their wishes fulfilled.

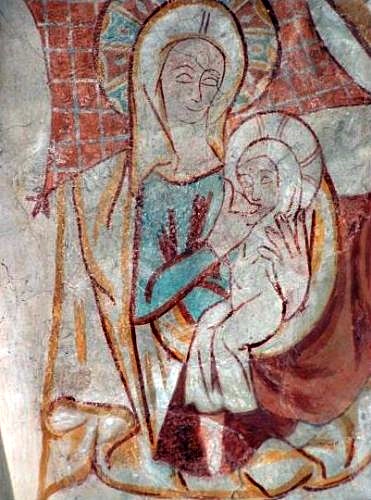

Fresco in Birkerød church, which shows the Virgin Mary breastfeeding the baby Jesus. Photo kalkmalerier.dk.

It says that clergy were exempted from the laws of the country: "Furthermore clergy are not to be sued for worldly tings or for worldly judges" . They were not to be taxed: "Furthermore the clergy and clergymen are not to be taxed." The king was not allowed to interfere in appointments to ecclesiastical offices: "Furthermore he may not present any clergyman to any church." In addition, the king was to deliver some estates and castles, which he had in his possession, back to the church - with this perhaps was thought especially of the fortress Hammershus.

Moreover, the king's income and fortune were reduced in so many ways that it probably knocked the legs away under Christoffer's ability to redeem Erik Menved's enormous debts. One must admire him for taking on the responsibility as king anyway:

"Furthermore, all knights and armsmen of their household are free to recieve fines of 3 marks and 9 marks", which apparently formerly went into the royal coffers.

The king was to redeem debts which the former king's men had guaranteed for his sake: "redeem all sureties for the now deceased king" and ransom "all who are in captivity for his sake".

He was not allowed to impose new taxes so that the citizens "could freely exercise their trading without the imposition of new burdens and duties, and they should be able to carry what they want to buy or sell out of the kongdom without custom duties on their goods."

And not only that. All burdens and taxes imposed since the time of King Valdemar were to be abolished: "Furthermore, the king's bailiffs may not impose on them (the peasants) untraditional taxes and burdens" and "Furthermore, the newly imposed burdens, every one, may not be collected in the future, namely ploughpenning, grain of gold, custom duties and everything else that has been imposed and invented after the death of King Valdemar."

Medieval market in Nyborg during the Danehof Festival in 2019. Photo Historisk Marked.dk

Moreover, the king could not independently introduce new laws: "Furthermore, new laws may still not be enacted, except with the consent of the whole kingdom at the next general meeting".

The king was not to go to war without the consent of the great men of the kingdom and of the bishops: Furthermore, the kng must not go to war against anyone without the advice and consent of the prelates and great men of the kingdom."

Many probably remembered Erik Menved's Swedish campaign. No one should have the duty to provide military service abroad, says the hand-binding contract: "Furthermore, they should not be forced to provide military service outside the kingdom". If they fell into captivity, the king "should immediately redeem them."

The park Borgvold in Viborg where one of Erik Menved's forced castles was located. Immediately after the adoption of the hand-binding contract, the four forced castles of Jutland were really demolished as intended. These were Kalø near Aarhus, Bygholm near Horsens, Voldstrup near Struer and Borgholm near Nørresø at Viborg. Photo 1001 fortællinger fra Danmark.

Erik Menved's hated forced castles in Jutland were to be demolished: "Furthermore, all castles in North Jutland must be demolished"

Besides, the hand-binding contract contained some national provisions: "Furthermore, no foreigner speaking an unknown language and not of the right age may be presented to any church," and "Furthermore, no German may possess castles, fortifications, positions or land, nor in any way have a seat in the king's narrow or sworn council". It was this national feeling that was to become the driving force in the reconstruction of Denmark during and after the kingless time.

But this "The king's narrow or sworn council" , which thus only was mentioned in connection with the ban on Germans among the king's men, was a very important constitutional innovation, which after Erik of Pomerania's time would completely replace the Danehof national meetings. The Kingdom's council, as representatives of the kingdom's best men, was to exist until Frederik 3. abolished it with the autocracy in 1660.

King Christoffer was hailed at the county tings in 1320, but he was not crowned because the archbishop, Esger Juul, was exiled abroad, and he had secured the pope's ban on any other bishop crowning Christoffer.

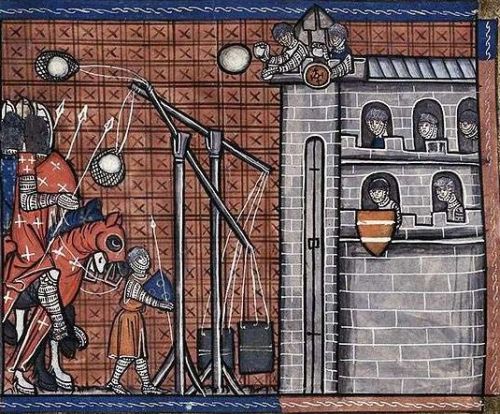

Siege of fortress in 1300's illustration. Stones are thrown at a castle with a throwing machine. Photo English Heritage.

Christoffer had great foreign policy success. A number of North German princes promised to support him with armed assistance in case of war. These were: April 8 1320 Erik of Lauenburg, June 11 1322 an alliance of several Pomeranian princes and July 17 1322 count Gerhard of Rendsborg-Holsten.

Erik Menved had in his time given his brother-in-arms, Henrik of Mecklenburg, the city of Rostock as hereditary fief. But at the news of Erik's death in 1319, Henrik refused to acknowledge the new Danish king and his men expelled the Danes from the "Danish tower" in Warnemünde.

But the many small principalities in northern Germany still regarded the Danish king as their natural rallying point in defense against the great principalities. In the spring 1322 Christoffer gathered several of the small northern German princes for a meeting in Vordingborg, where they formed a coalition against Henrik of Mecklenburg. These were the princes of Saxony, Werle, Schwerin, Pomerania, Holstein and several others, as well as the said Rügen.

In reality, Christoffer went to war against Mecklenburg in secret. There is no evidence that he had obtained "the advice and consent of the prelates and great men of the kingdom.", as prescribed by the hand-binding contract.

Christoffer 2's seal. Photo: Illustration by Professor Julius Magnus Petersen (1827–1917) in "Et dansk Flag fra Unionstiden i Maria-Kirken i Lübeck" Wikipedia.

Henrik of Mecklenburg soon saw himself surrounded by enemies, small enemies admittedly, but they were many and he knew that it was Christoffer who pulled the strings from Vordingborg.

He made contact with some of Christoffer's enemies to the north. It was about Knud Porse, a nephew of the outlaw from 1286, Peder Porse, and Erik Menved's exiled drost, Niels Olufsen Bildt. Together they tried to get Sweden to go to war against Denmark.

But the council of the Swedish kingdom did not want to hear anything about war, on the contrary, they sent unsolicited message to Denmark and promised to keep the peace.

However, Knud Porse succeeded - perhaps in 1322 - in persuading a number of Scanian nobles to rebel against the king. But Christoffer sent his skilled marsk, Peder Vendelbo, to Scania and the revolt was completely defeated. Several Scania nobles were executed, others were fined and their estates confiscated.

Historian Palle Lauring mentions that then the ploughpenning was relentlessly collected. And it was explicitly forbidden according to the hand-binding contract, which specifically mentions that "ploughpenning" should not be collected.

"Here King Karl battles with the heathens". Picture from around 1334 which is incorrectly called "The Battle of Mühldorf" from a manuscript for the knight novel Willehalm. Foto Wikipedia.

The general political development in Germany came to Christoffer's aid. There had been a dispute over the imperial throne for years, but in one of the last great knights' battles of the Middle Ages near the Mühldorf am Inn in September 1322, Ludwig der Bayer of the Wittelsbach family won.

One of the first acts of government of the new emperor was to install his eight-year-old son, also named Ludwig, as Margrave of Brandenburg. To give the son political support, the emperor proposed on behalf of the boy to Christoffer's eldest daughter, Margrete. King Christoffer answered yes and promised to give her a dowry of 12,000 marks of silver.

Faced with this new alliance consisting of Bavaria, Brandenburg and Denmark, Henrik of Mecklenburg threw in the towel and arrived in Vordingborg, praising Christoffer as his lord. Prince Wizlav of Rügen also confirmed his allegiance to his lord.

The fortress Hammershus on the island of Bornholm. Foto Visual Bornholm.

Erik Menved's former marsk, Ludvig Albrechtsen Eberstein, was one of Denmark's and Christoffer's great creditors. He had Scania as a pawn fief for more than 6,000 marks of silver. With great concern he had witnessed Christoffer's active policy in northern Germany and not least his promise to give the emperor 12,000 marks in dowry for his daughter.

Historian Palle Lauring writes that Ludvig Albrechtsen had supported the uprising in Scania in 1322, and this was the reason or possibly the pretext that Christoffer had him convicted outlaw - perhaps in 1323.

The year before Erik Menved's death, in 1318, Ludvig Albrechtsen, as his marsk, had conquered the fortress of the exiled archbishop, Hammershus and he still had it in his possession at Easter 1324, when a royal army arrived on Bornholm and began a siege.

But the siege was to last 16 months, and while it was going on, Christoffer had other things to think about.

As had previously been the case in connection with other rebellious archbishops, a papal representative came to Denmark precisely in 1324 to negotiate a settlement between Archbishop Esger Juul and King Christoffer and this time he really succeeded in negotiating a settlement. The king was to give the archbishop the castle Hammershus - which fortress was not yet in the king's possession - and all his estates back, which Erik Menved had confiscated. But the bishop was not to receive any further compensation and further was to pay Ludvig Albrecktsen, what it by that time had cost him to conquer the castle.

Collection of taxes in the Middle Ages. Photo Yandex.

On 15 August 1324 all problems were resolved between the king and the archbishop, and the archbishop was able to crown Christoffer as king of Denmark in Vordingborg with his eldest son, Erik, as fellow-king - as was the custom of the Valdemars.

At Christmas 1324 there was another party at Vordingborg Castle, because the young Margrave of Brandenburg came to bring home his bride.

But the first installment on the large dowry fell due at the same time for payment and Christoffer had to charge new special taxes - what was expressly not allowed according to the hand-binding contract under at least two paragraphs: "Furthermore that they may not be taxed without mercy," and "yet the king's bailiffs shall not impose on them unfamiliar taxes and burdens."

In the year 1325, Archbishop Esger Juul and also two of the kingdom's princely nobles, Prince Wizlav of Rügen and Duke Erik of Southern Jutland, died, which last event aroused the Holsten counts as they considered it theirs. historical duty to maintain this rich and fertile province as a duchy beyond the reach of the Danish kings.

Most German principalities had become increasingly smaller during the Middle Ages, because over time they had been divided into several smaller principalities, as more sons each had to have their share. In Christoffer 2's time, Holsten was divided into Count Gerhard's Holsten-Rendsborg and Johan the Mild's Holsten-Plön or Holsten-Kiel.

Holstein was without a doubt very fertile, but not more fertile than Denmark. As can be seen, it was a fairly small area compared to Denmark. One must wonder how such small areas could generate wealth enough for the counts, to have practically all of Denmark as pawn fiefs. Where were the secret gold and diamond mines? The only explanation that can be found is that the Holsten counts were skilled and experienced mercenary commanders who had made a lot of money by fighting for other princes, for example Erik Menved of Denmark.

Count Gerhard of Holsten-Rendsborg immediately put himself in place as guardian of the late Duke Erik's 10-year-old son, Valdemar. King Christoffer could have prevented this and appointed himself guardian of the minor duke, as both Christoffer 1. and Erik Klipping had done in similar situations, which would have been natural, since he was after all a Danish king with great interest in South-Jutland, one might think. But quite unusual for him, he preferred to step back and avoid confrontation.

One spring day in 1326, Count Gerhard and his young nephew met the former marsk, Ludvig Albrecktsen Eberstein, and the drost, Lars Jonsen Panter, in Sønderborg. They all had pawn fiefs and money for good with King Christoffer. Count Gerhard of Holstein had Funen as a pawn fief or at least part of the island, Ludvig Albrecktsen believed to have Scania and Lars Jonsen Panter believed to have the right to the island of Ærø as a kind of second-hand pawn fief. They feared - probably rightly - that King Christoffer did not intend to pay, and therefore they agreed to proclaim a rebellion against the king.

Before Christoffer could react, the whole of Jutland and Fyn was in revolt at the same time as Prince Vartislav of Pomerania threatened to take advantage of the situation and acquire the island of Rügen.

Christoffer's eldest son and fellow-king, Erik, was enclosed in the castle Tårnborg near Korsør by his rebellious Danish army. There are no indications that it should have been a very strong fortress, probably it was only a tower surrounded by palisades, as an unfortunately unknown artist has depicted it here. Photo: Illustration in Roskilde Development of how the artist imagined Haraldsborg near Roskilde.

King Christoffer summoned his German vassals, who had promised to help him in war. They met in Nykøbing Falster, where Henrik of Mecklenburg and the princes of Werle promised to field an army of 800 armored riders for a payment of 12,000 marks of silver in cash and 15,000 to pay later. The princes conditioned themselves on getting Lolland, Falster and Møn as pawn fiefs for the remaining debt.

While Christoffer waited for the rescue army, he ordered leding on Sjælland and in Scania and reinforced the peasants' army with a corps of German mercenaries. His young co-king, Erik Christoffersen, led the army towards Korsør.

But the Danish part of the army suddenly turned against the young Erik, and he was enclosed in the castle of Tårnborg near Korsør with his loyal German soldiers. He had not foreseen such a development and was not at all prepared for a prolonged siege, and after two weeks he had to give up and surrender, and then he was taken to Haderslev in chains.

Lübeck Chronicle describes Erik: "whose mind was fierce and speech foolish" .

Already the following night, Christoffer fled under cover of darkness to northern Germany with Queen Eufemia and their youngest son, Valdemar, who would later become known as Valdemar Atterdag.

But just over a month later, Christoffer and Henrik of Mecklenburg returned with the promised rescue army of nearly a thousand armored riders, it is said.

Vordingborg old castle area with the Goose tower. Photo A.P. Møllerfonden NH Luftfoto & Video.

However, Count Gerhard was an experienced army commander, and before long Christoffer's large army was enclosed in Vordingborg without sufficient supplies for either men or horses.

Henrik of Mecklenburg managed to escape from the city and come to Count Gerhard at his headquarter on the island of Bogø. Here Gerhard offered him compensation for his claim against King Christoffer - which he would not get if he failed him - and a little more. That decided the case, and Henrik returned to Vordingborg and informed Christoffer that from now on he had to do without him.

King Christoffer reluctantly left Vordingborg and tried for a time to settle on Falster, but finally had to - still in 1326 - return to northern Germany.

A contemporary chronicle - probably the monk Thomas Gheysmer's continuation of Saxo's Danish Chronicle - wrote that shortly after the castle commander sold Vordingborg Castle itself to Count Gerhard and "then the king no longer had a patch of land in the kingdom where he could set his foot."

Already on June 7 1326 the conspirators from Sønderborg did their next move. They proclaimed the 11-year-old Duke Valdemar Eriksen of Southern Jutland King of Denmark at Viborg Ting, probably while King Christoffer was still in the country.

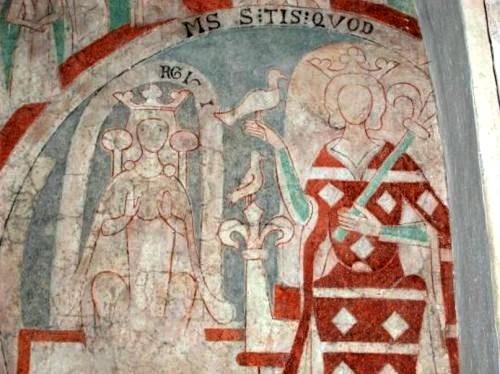

Fresco in Kelby Church on the island of Møn from 1325 which shows a royal wedding. The king carries the lily stick, which represents the true Catholic faith, in his left hand and holds a falcon in his right. In addition, there is another lily stick on which sits a falcon. Foto kalkmalerier.dk

On the same day and in the same place, the young king signed a hand-binding contract, which was very similar to the one that Christoffer had signed six years earlier. The only difference was that the king's authority was further limited, as almost all royal castles in Scania had to be demolished to the ground, while nobles and citizens were allowed to fortify their castles and cities as they wished.

When Christoffer had finally escaped the kingdom, the conspirators and their followers led their puppet king around to Denmark's other county tings, where he was hailed as Valdemar 3.

At the forthcoming Danehof in Nyborg, presumably in 1327, the young king expressed his heartfelt thanks to his "uncle Gerhard" for his selfless help. He then appointed Count Gerhard duke of his own former duchy of Southern Jutland. Count Gerhard thus became Denmark's most powerful man with three titles, Count of Holsten-Rendsborg, Duke of Southern Jutland and Governor of Denmark.

In addition, the Count persuaded the Danehof Assembly to adopt the binding promise that "the duchy of Southern Jutland should never be able to be reunite with Denmark"..

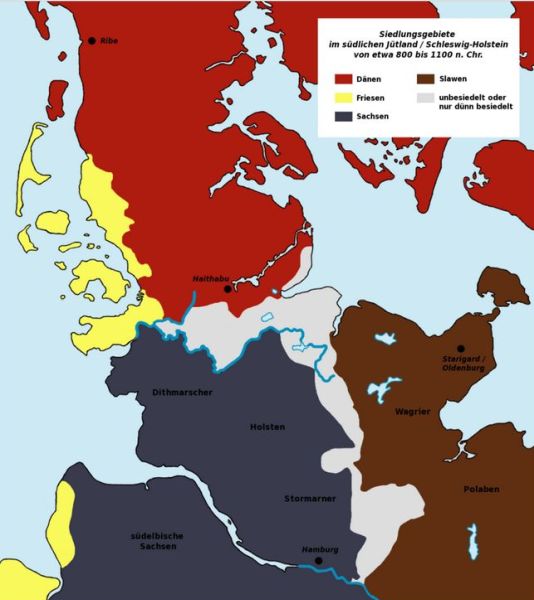

Original native languages in Southern Jutland and Holsten according to place names. Red represents Danish, yellow stands for Frisian, dark blue represents Saxon and brown stands for Slavic, empty areas are light gray. Sources:

1) "Siedlungsgebiete vom 9. bis 11. Jahrhundert" in: "Historischer Atlas Schleswig-Holstein vom Mittelalter bis 1867", Neumünster 2004.

2) Peter Ilsøe: "Nordens Historie", København 1936; note: The coastline is only approximate as it is from early modern times. Photo JulieMom Wikipedia

When Ludvig Albrecktsen Eberstein and Lars Jonsen Panter so easily gave away Southern-Jylland for always, it was in the cards that they should be rewarded. Ludvig received a good part of the Central Jutland and the Scania market as security for outstanding receivables, while Lars Jonsen had to satisfy with Langeland and Ærø.

In 1327 there were sales on all shelves. Everything could be done.

Count Johan of Holsten-Plön thought he was entitled to Fehmern, Lolland and Falster, which claim was granted. A Swedish prince presented inheritance claims after Erik Ploughpenning, which was complied with with some estates.

There was an independent knight in Halland, named Knud Porse, who was a relative of one of the outlaws from 1287, Peder Porse. He had joined the service of the Swedish Duke Erik, who died in such a tragic way in the infamous Nyköbing Gästbud in 1317.

In 1326, Peder Porse was commander of Varberg Castle in Northern Halland, and in the castle lived Duke Erik's widow, the Norwegian princess Ingeborg, and her little son Magnus, who had been elected king of both Norway and Sweden. Knud Porse wanted to marry Ingeborg, but it was a hopeless love as the difference in status was too great for them to get married.

But in the general confusion in 1326, Knud Porse managed to put himself in possession of both South-Halland and Samsø. At a subsequent Danish meeting for the whole kngdom on Fyn in 1327, the new king, Valdemar III, appointed him Duke of Halland and Samsø, and therefore he could only a year later - by virtue of his now princely status - marry the princess.

"Southeast of Hedehusene where Torslunde Bro crosses Vejle å" it says in the chronicle. Thorsbrovej sounds like a very old name. Torslunde Bridge may have been where this road crosses Lille Vejle Å. However, the author does not believe that there is enough water in the river that it is possible to drown in it. Photo Google Maps.

"Woe to the land whose king is a child" a contemporary chronicle wrote, probably the monk Thomas Gheysmer's continuation of Saxo's Danish Chronicle. " the devil has come before God and he has distributed the land with his measuring rope." For what good was it that the king was bound by many hand-binding contracts, when a clique of great men ruled as they saw fit, no one had demanded any hand-binding contracts from them from them.

On Sjælland, the general enthusiasm over the expulsion of Christoffer soon cooled, especially when the pawn fief holders collected extra taxes perhaps in 1327-1328. The peasants found their weapons and rebelled. Count Gerhard gathered a force of Holstenians and Danish nobles and met the peasants' army "southeast of Hedehusene where Torslunde Bro crosses Vejle å". The peasants could not withstand the well-equipped and experienced soldiers and horsemen but were pushed back. Only the luckiest escaped the confusion, while the rest fell or drowned in the river, it is said.

Hestebjerg with a view of Slien and the Viking tower. Photo Slesi Wikipedia.

In 1329, the Bishop of Ribe, Jacob Splitaff, assembled an army of disgruntled Jutland people and invaded the duchy. They captured and burned the castle, Hadeslevhus, and then attacked Gottorp on Palm Sunday 1329. but were beaten back.

The followers of the bishop of Ribe, however, gathered for a new attack and already had Gottorp in sight, when Count Gerhard arrived with his army and repulsed them at Hesterbjerg near the town of Slesvig near Gottorp.

But the counts Gerhard and Johan were becoming uneasy about the whole project with the child king Valdemar 3. In order for them to be able to get their money, there had to be orderly conditions. The historian Erik Kjersgaard quotes a chronicle for writing about Count Gerhard: "He clearly realized that the Danes were very unsteady in their actions."

In 1329 Count Johan the Mild of Holsten-Plön met with his half-brother, Christoffer, in Lübeck and offered to help him back to Denmark as a king, however against payment of 20,000 mark with pawn fief of Lolland as security. Christoffer was very interested. Count Johan presented the case to his cousin, Count Gerhard of Holsten-Rendsborg, who, however, conditioned himself that Johan should guarantee Christoffer's debts, but otherwise he had no objections.

In the summer 1329 Christoffer and Johan went ashore at Vordingborg with an army of hired knights. The castle commander welcomed them. But the Sjælland nobles, led by Knud Porse, ordered the peasants to mobilize for protection against the foreign invasion.

King David kills Shobach, commander of the Syrian army. Photo Maciejowski Bible, allegedly from 1244-1254, New York, Pierpont Morgan Library.

As the Sjælland army approached Vordingborg, Christoffer - taught by costly experiences from the castle's previous siege - chose to fight his way through. The gate of Vordingborg Castle opened and an army of armored knights streamed out. Knud Porse and 300 other nobles discreetly withdrew in the background while they watched the peasants' army being destroyed. Since then, he joined Christoffer.

During the army's further journey across Sjælland, Christoffer received word that Copenhagen would open its gates to him. But Johan also got word of this news and sent a group in advance, which pretended to be the king's men. They hoisted the Holsten banner with the "nettle leaf" over the castle. When Christoffer and the rest of the army arrived and saw this, he realized that what the child-king had been to Count Gerhard he should be to Johan. The count took it easy and then afterwards referred to Christoffer only as "the former king".

However, Ludvig Albrectsen Eberstein had died and Johan managed to negotiate so that his widow gave him two valuable assets, namely Helsingborg Castle and Ludvig's prisoner of war from Tårnborg in 1326, Christoffer's eldest son and fellow-king, Erik Christoffersen.

At a meeting in Ringsted, Count Johan demanded all of Denmark east of the Great Belt as a pawn fief and also the taxes from Jutland. Christoffer agreed it all and the only thing he achieved in return was his son's freedom.

In 1330 Christoffer changed horses, and he and Erik traveled over to Jutland, where they met Count Gerhard. They agreed on some important changes. Christoffer was recognized as king, the 15-year-old Valdemar 3. was deposed and returned as Duke of Southern Jutland, Gerhard was recognized as Duke of Funen and the agreement was to be sealed by the young Erik Christoffersen marrying Count Gerhard's sister.

King Christoffer established his Jutland residence in Skanderborg.

While in Jutland, in 1330 his faithful queen, Eufemia, died after 30 years of marriage, who had loyally followed him in his ups and especially downs.

Børlum Monastery southwest of Hjørring. Photo Løkken Familie Camping

In Vendsyssel, Bishop Tyge Klerk of Børlum ruled sovereignly. He grossly neglected his ecclesiastical duties. He had thrown monks and canons out of the monastery and turned it into a fortress. He had seized the royal estates and had begun to collect taxes. When some German merchants stranded on the West Coast, he assaulted them on the beach and robbed the goods they had painstakingly rescued ashore. There were stories that people had seen the bishop himself break open the ship-chests with an ax and "with his knife he cut the shipwrecked men's purses from their belts and trousers to get their contents"

King Christoffer stopped his excesses and threw him into prison, but he received no thanks for that. The pope never the less declared Denmark in an interdict because he had imprisoned a bishop. However, it did not have any practical importance, as the priests did not follow the pope's order.

Fresco in Østerlars Church on Bornholm from 1325, which shows the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus in the stable in Bethlehem. Photo kalkmalerier.dk

In 1331 there was a war between the two giants, Count Gerhard of Holsten-Rendsborg and Count Johan of Holsten-Plön.

King Christoffer again changed sides and chose to support Johan. Together with his sons, Erik and Otto, he marched down through Jutland at the head of a mixed German-Danish army of 750 men to attack Count Gerhard in his homeland.

When the count heard news that Christoffer was on his way south with a numerically superior force, he hurried north and took up position on Kropp Hede a little north of the Danevirke.

In the morning, Tuesday 29 November 1331, Christoffer's army approached Danevirke and there they saw a small group of soldiers, who had taken up position in close formation on a small hill some distance from the road. It soon became clear that it was Count Gerhard and his men.

Christoffer hastily gave the knighthood to some of his men and then gave orders for attack. The Count remained on the defensive and resisted attack after attack. Towards evening, Christoffer's men began to grow weary, and the attacks became increasingly slack. Then Count Gerhard took the offensive and Christoffer's army disbanded and tore the king and his sons with him in the flight.

Thanks to a grant from A.P. Møller and Wife Chastine Mc-Kinney Møller's Foundation for General Purposes - Museum Sønderjylland, in collaboration with the Archäologisches Landesamt Schleswig-Holstein, has succeeded in finding and excavating the gate in Danevirke mentioned in the Frankish Annals in 808. The gate is connected to the so-called boulder wall from the 700's and is found quite close to the Danevirke Museum. Photo pilgrimsvandringen.dk.

They wanted to ride south and seek refuge with their ally, Count Johan, in Kiel, but in the crowd as they rode through the old gate in Danevirke, Erik's horse collapsed under him, and he was fatally wounded. Christoffer's second son, Otto, was captured by Count Gerhard.

Shortly after the New Year, on 10 January 1332 , Gerhard arrived in Kiel and in the subsequent negotiations he demanded and got the whole of Northern-Jutland and Fyn as a pawn fief for a redemption sum of 100,000 marks of silver, which in reality would say that these countries were not redeemable. Count Johan gave up his alliance with Christoffer and revaluated his price of Scania, Sjælland, Lolland and Falster to also 100,000 marks of silver if these lands were to be redeemed. Christoffer was allowed to keep his royal title, for only a king could sign such claims on behalf of the country.

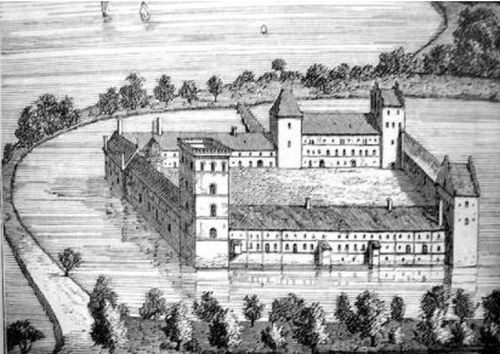

Aalholm Castle near Nysted on Lolland where Christoffer was imprisoned for some time. Drawing by Peder Hansen Resen.

He left his sick son in Kiel and went to the Christoffer family's homeland, Lolland-Falster, where he, through Johan's intervention, was allowed to live in an ordinary house in Sakskøbing on the island of Lolland. Soon after, he was informed that his son, Erik, had died in Kiel from his injuries.

Two Danish nobles, Hennike Breide and Johan Ellemose, tried to burn him inside the house in Sakskøbing, but he survived by jumping out of the window, where he was arrested and then imprisoned in Aalholm Castle near Nysted.

However, Count Johan did not reward the potential murderers for this crime and made sure that Christoffer was released and allowed to live in a house in Nykøbing Falster until his death.

After his death, no new Danish king was elected, and it seems as if Denmark was destined to disintegrate in the throng of small German principalities.

Christoffer was the second son of Erik Klipping and Agnes of Brandenburg. Erik Menved was his big brother.

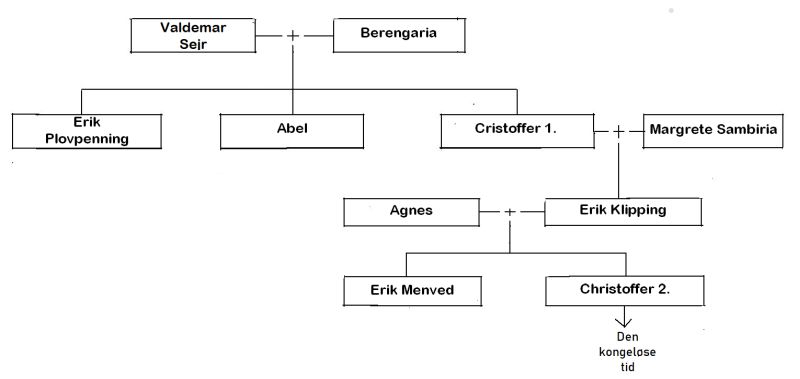

Simplified family tree for the Valdemars from Valdemar the Victorious to Christoffer 2.

Erik Ploughpenning, Abel and Christoffer 1. were sons of Valdemar the Victorious and Berengaria and they all became kings, one after the other. Erik Klipping, who suffered death in Finderup Barn, was the son of Christoffer 1. and the famous Margrete Sambiria. His sons with Agnes of Brandenburg were Erik Menved and Christoffer 2. who both became kings. Of these seven kings, only three died a natural death.

In the year 1300, Christoffer married - at the age of 24 - the 15-year-old Eufemia of Pomerania, who was the daughter of Bogislaw 4. Duke of Pomerania. She followed him faithfully for 30 years both as duke, king and as exiled king until she died in 1330, while she and Christoffer stayed in Skanderborg.

Eufemia and Christoffer had six children together, as we know about:

Euphemia of Pomerania in detail from her tomb in Sorø Klosterkirke. It was made quite shortly after her death and most likely it has portrait likeness. Photo Mariusz Paździora Wikipedia.

- Margrete 1305–1340, who married Ludvig 5. von Wittelsbach, Margrave of Brandenburg and Duke of Bavaria. At the wedding she was maybe 18-19 years old and the groom was 10-11 years old.

- Erik 1307–1331, who at the age of 17 was crowned as his father's fellow-king in 1324. He fell into captivity by Ludvig Albrechtsen Eberstein in 1326 and was not released until three years later. He died of his wounds in 1332 after the battle at Kropp Hede at the age of 25 years.

- Otto, 1310-1347, fell into captivity with Gerhard of Holsten-Rendsburg after the battle of Kropp Hede in 1331, but was soon released. He was again taken prisoner by the same Gerhard in 1334 in an attempt to be elected King of Denmark, and was then held prisoner in the castle in Segeberg in Holsten, until he was released in 1341 on condition that he recognized his little brother, Valdemar, as King of Denmark. In 1346 he joined the German Order in Estonia. His further fate is unknown.

- Agnes 1312, who died as a child.

- Helvig 1315, who may also have died as a child.

- Valdemar 1320–1375, who since 1326 grew up with his older sister at the imperial court in Brandenburg and became king of Denmark with the byname Atterdag.

A sister of Christoffer 2. and Erik Menved was named Richiza, and she married Nicolaus of Werle and had a daughter, Sophie of Werle, who married that count Gerhard of Holsten-Rendsborg, who got the whole of Western Denmark as pawn fief and who died for Niels Ebbesen's hand in Randers in 1340. It is through her that the Oldenburg royal lineage descends from the old Danish royal family, as Christian 1. who became king of Denmark in 1448 - and was the first king of the Oldenburg family - was the great-grandson of Sophie of Werle and Count Gerhard.

In August 1332 Christoffer 2. died alone in an ordinary house in Sakskøbing on Lolland that Count Johan had made available to him. He turned 56, which is more than most men of his time. His wife had died two years before, his eldest son, Erik, had died of his wounds and his second eldest son, Otto, was in Holstenian captivity. His youngest son, Valdemar, who at this time was only 12 years old, he had probably not seen in the last three years, was staying with his older sister at the Imperial Court in Brandenburg.

Christoffer 2's bronze tomb in Sorø Monastery Church. Here he is buried by the side of his queen, Eufemia. Photo: Lindas-netsted.

Already as a duke, Christoffer gave Sorø Kloster a gift certificate, which obliged the monastery to bury Eufemia and himself in front of the altar in the monastery church. He wanted to be buried precisely in Sorø Monastery church, because he wanted to lie next to his little brother, Junker Valdemar, who was buried there in 1304.

Junker Valdemar did not want to be buried in Skt. Bendts Church in Ringsted, which was otherwise the burial church of the Valdemars, because he was in such fierce conflict with his brother, Erik Menved, that he would not lie in the same grave as him.

Eufemia's and Christoffer's original tomb monument in Sorø was paid for by their son, Valdemar Atterdag. The modern tomb monument was made by Johannes Wiedewelt in 1776-77 to replace an original monument. However, the two lying bronze figures are original. There is also a small bronze figure, who can imagine is a child that we do not know about.

They lie nearby their eldest son, Erik, and the two little girls, Helvig and Agnes, a relative named Albert and as mentioned above Christoffer's little brother, Valdemar.

| To start |